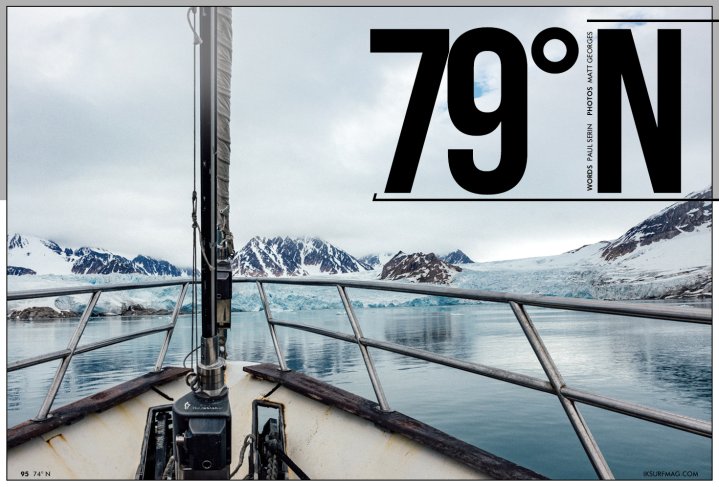

79°N

Issue 95 / Wed 5th Oct, 2022

Imagine spending 12 days with 11 crew and 20 board bags on a 25-metre vessel. Even more, imagine sailing that vessel to an environment so icy and harsh that only polar bears and reindeer want to live there - and then going kiting! Paul Serin documents the MANERA team’s incredible expedition to Svalbard, and tells extraordinary tales of kiting between icebergs and in front of glaciers in this IKSURFMAG exclusive!

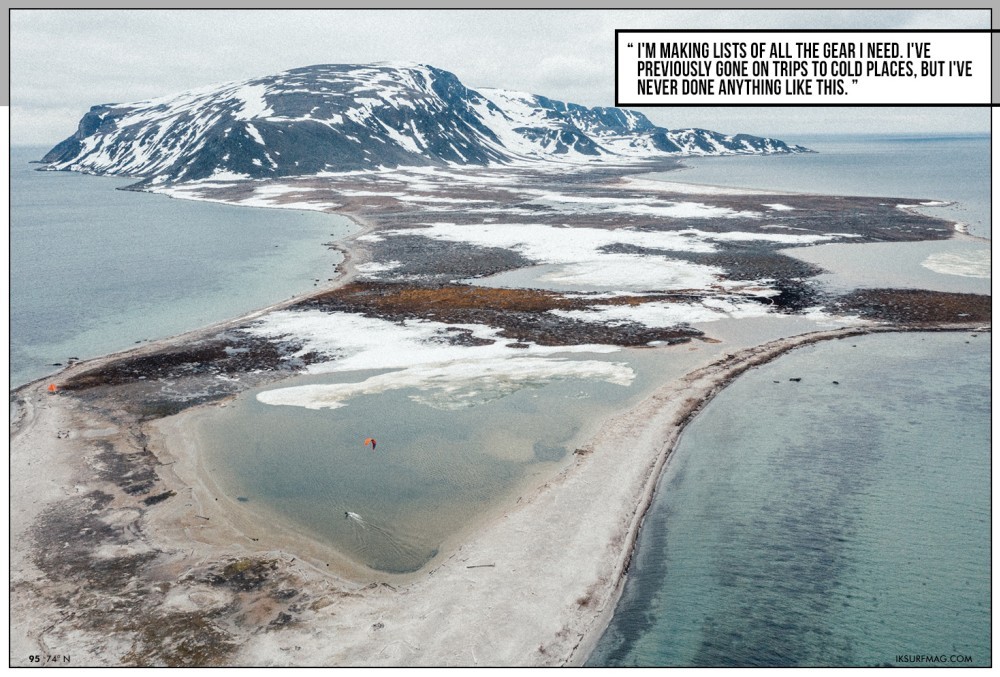

D-day is approaching, and my excitement is through the roof. This trip was two years in the making, and it is finally happening. I'm increasingly worried about forgetting something, so I'm making lists of all the gear I need. I've previously gone on trips to cold places, but I've never done anything like this. To tell you the truth, I still have a hard time comprehending where we are going.

A documentary is running on my computer while I continue packing. Base layers, ski socks, ski gloves? Do I really need ski gloves? Rather than ask, I take them. Just in case, as they say. That's something I say with just about every accessory I add to my bag, on top of my winter jacket and ski pants.

Where exactly are we going? To Svalbard, an archipelago located north of Norway. The islands range from 74° to 81° north latitude. Keep in mind that the Arctic Circle is very close at 66°30' N. The people I talk to don't really realise where it is, and I don't think I do either. I don't go into details when they ask, "So, Paul, where is your next trip?" I just reply, "On an island north of Norway," and let them imagine what they want.

Like every trip I've been on since I began kiting, there are many boardbags involved. With MANERA, there are always a lot of them, and the airlines must truly hate us. But you don't want to leave it up to chance on a trip like this. You have to be ready for anything. I don't know what scares me the most: the cold, or the idea of spending 12 days on a boat between the Greenland Sea and the Barents Sea.

The trip starts with a stop in Oslo, the Norwegian capital. We wait for the whole team to arrive before leaving for Longyearbyen, the "biggest" town on Svalbard with around 2,500 inhabitants. Our pit stop here feels a bit like a decompression chamber before the real cold, and the real adventure.

As for the riders, Mallory "Mallo" de la Villemarqué and Matt Maxwell are coming for strapless kite and wave, and Fernando "Mizo" Novaes for surf foil and wing. On the media team, Olivier Sautet is our videographer, and Matt Georges is our photographer. Anthony Lietart is here as well to film everything happening backstage during the trip. And, of course, Julien Salles, MANERA's boss and without whom none of this can be possible, oversees the trip. And finally, there is me, Paul Serin, mainly for twin tip and freestyle, and some wing foil.

Our arrival in Longyearbyen does not go unnoticed. The other passengers on the plane think we are scientists because of all our big bags. When we explain that we are here to kite surf, their eyes widen, showing both astonishment and compassion. Yes, we will kitesurf in one of the most extreme and northern places in the world. Just writing these words gives me goosebumps.

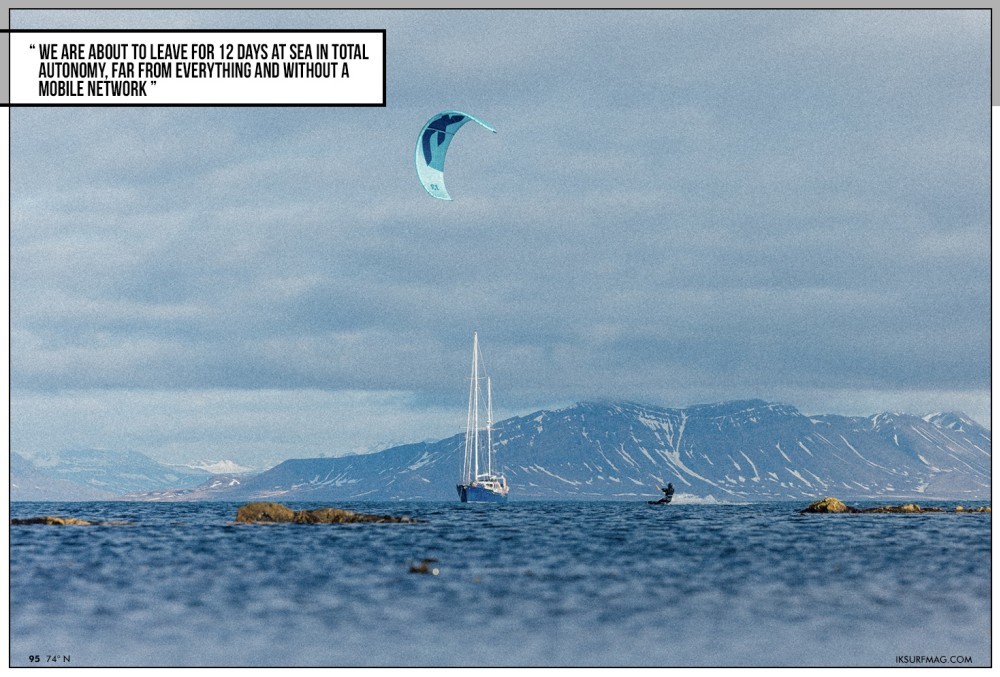

For the next two weeks, our floating house is called Kamak. She is a 25-metre-long boat coming from Paimpol in Brittany. She normally hosts ski trips between Svalbard, Greenland, and Norway, but this time, the action will take place on the water and not in the mountains.

With the crew, there are 11 of us in total. Stress is starting to build. Are we going to get along well in such a small space for 12 days?

Gaby, the captain, manages his boat perfectly. We also understand quite quickly that he is a little bit obsessive when it comes to tidying up. I personally don't have a problem with that, but with 20 boardbags, cameras and all their chargers, it can get out of hand pretty quickly. He is assisted by Jean, a young Breton sailor familiar with the cold and expeditions of this kind. Last but not least, Minh is the cook. Despite his shyness, he will be the decisive asset of this trip and responsible for the good mood of the group.

The boat is almost ready to go. I help Minh with the last shopping trip to the supermarket. We are about to leave for 12 days at sea in total autonomy, far from everything and without a mobile network: just us and the grandness of nature.

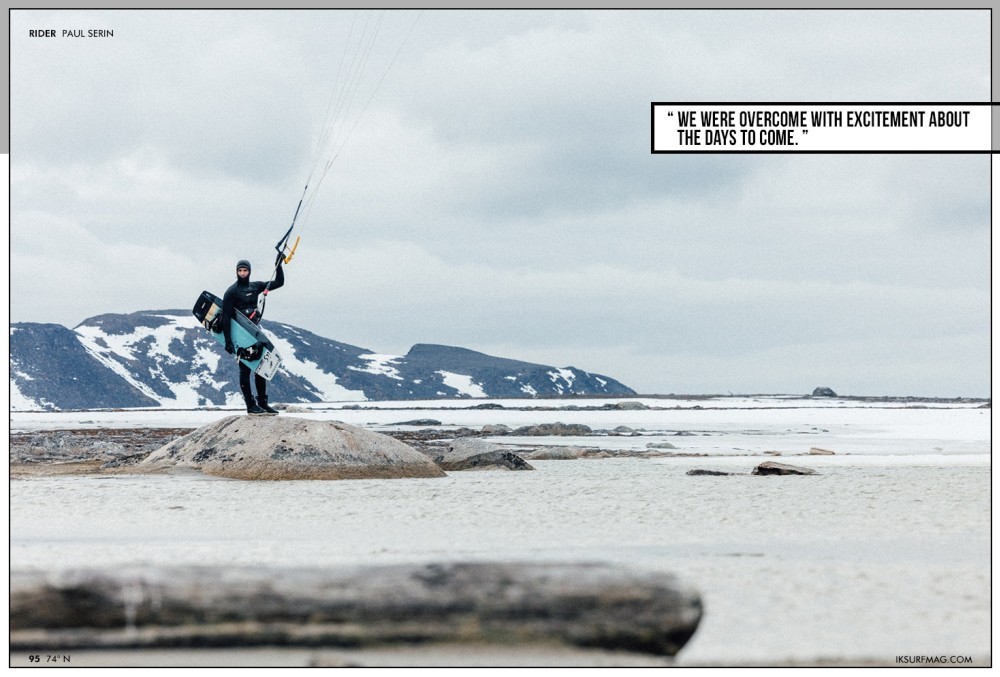

Finally, we cast off, and the real adventure begins. We are heading straight north. We all gather next to the captain's screen to try to figure out exactly where we are going. Our first stop will be just outside the Longyearbyen Fjord, where we will have our first session.

I step out onto the deck and look around. The air is frigid on the only part of my face that isn't covered, but my eyes are in awe of the scenery. The sun is out on this first day. I have a hard time wrapping my head around the fact that it never sets at this time of the year. After three or four hours of sailing, we finally arrive at the first spot. The wind blows gently, the area looks clear, all lights are green.

Another essential detail to mention is that on Svalbard, there are about 2,500 inhabitants and 3,000 polar bears, so the chances are high for us to see one. Of course, our goal is for that to happen while on the boat, and not on land while inflating our kites. The groups of skiers who usually come here are always accompanied by an armed guide to protect them in case of an attack. Our only defence tools are a flare gun and binoculars. Before we land on any beach, we have to scan the horizon to ensure there are no big, white fur balls around.

The first session starts slowly. I put on my 6.4mm hooded wetsuit and my 5mm booties without forgetting my pair of gloves. It is impossible to start with a kite from a sailboat because of the shrouds and the limited space. However, Mizo can easily take off with his wing, so he will be the first in the water.

I get into the dinghy with Mallo, and Jean takes us to the beach. The landing area is slightly below a small hill, so we can't see if anything is up there waiting for us. As soon as we set foot on the ground, Mallo and I instantly look at each other, the same idea obviously having crossed our minds. We sprint up the hill to see what's above us, brandishing our kite bars and screaming, driven by a surge of unconsciousness.

No white-haired animal is waiting for us up there. On the other hand, reindeer antlers and the immensity of nature are. Once the adrenaline rush is over, we get into the water. It is cold, and the wind is light, but the sun feels so good.

I take my time to ride and enjoy the landscape. The mountains are high and steep, and the plains stretch as far as the eye can see. I feel like an ant in a world of humans. I imagine the potential creatures that could be underwater in such a remote corner of the world. But as soon as these thoughts cross my mind, I immediately turn around to get closer to the boat.

The first session of a trip is always quite special. It sets the tone and prepares us for the rest of the journey. Getting out of the water, I dread the moment when I will need to take off my wetsuit. Fortunately, my body is still relatively warm, so the transition from wetsuit to poncho is not so bad.

Ten hours of navigation are now ahead of us to reach the north of Svalbard and the 79th parallel north. The headwinds force us to turn the engine on to keep moving forward. But one of the advantages at this time of year is that there will be no night sailing, as it is daytime 24 hours a day.

The first dinner is joyful. It's a treat to eat Minh's dishes, which he also makes in great quantity. With this group of hungry guys, it is something crucial to keep in mind. I, however, can only swallow a bit of soup before the boat starts swaying again. I decide to leave at once to lie down in my bunk.

A few hours later, the noise of the anchor chain briefly wakes me up. It is only midnight, but the boat is not moving anymore. It's calm again. I later find out that we still have a long way to go and that we would not ride that day. The goal is to reach the northernmost point of Svalbard and then sail around this region, depending on the wind.

The cellular network has left us for good. Strangely enough, we all suddenly feel closer to one another. No more phones vibrating on the table during meals, nor "Wait, I'll check on Google if it's true". We are back to the essentials: us, the boat, the trip.

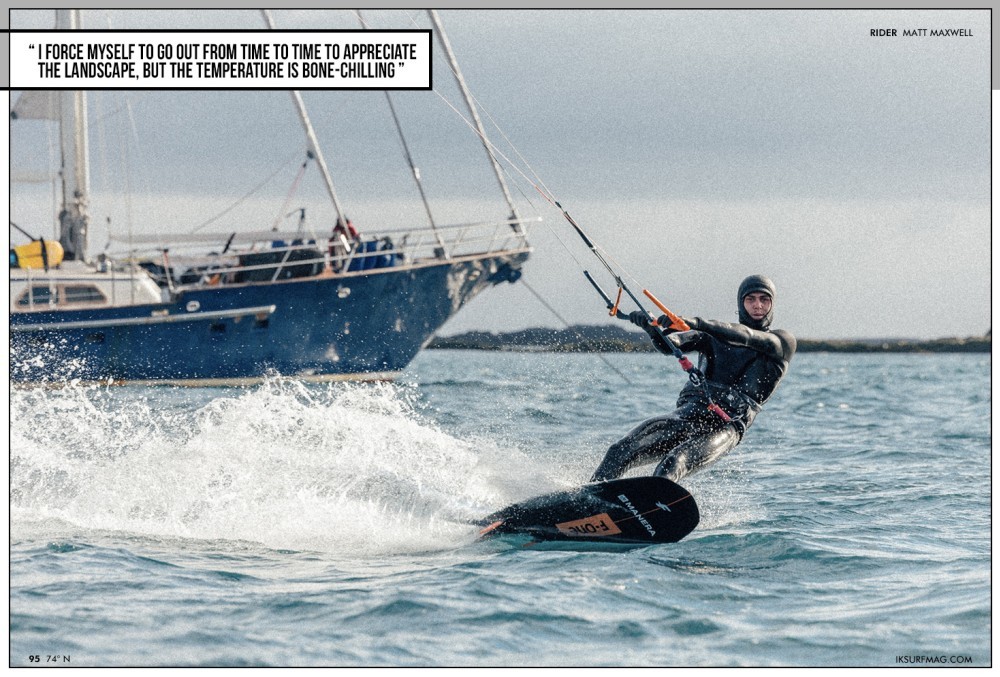

We try to fill this day as best as we can with meals, card games and a long nap. I force myself to go out from time to time to appreciate the landscape, but the temperature is bone-chilling, and my eyes immediately start watering. The air reminds me of a day of skiing in the Alps, so cold and dry that my throat freezes with every breath.

We make headway little by little, but our current GPS point always feels so far away from our destination. We end up sailing for 15 hours instead of 10. A wave of relief washes over us when the captain announces that we have finally arrived. On the map, we can see the beginning of the sea ice, which is only a few kilometres away. The GPS indicates the long-awaited 79 North. It hasn't really hit me yet; I just know that we are very, very far up north.

The hours don't really have any value anymore. I put my watch away in my bag. Only meals punctuate our days. It's been a week since we left our homes. But apart from a short session on the water, not much has happened. Even though we all know that it's part of the game on MANERA trips, it's still hard to look to the future, especially in such a cold and hostile place where the wind forecast changes every two hours.

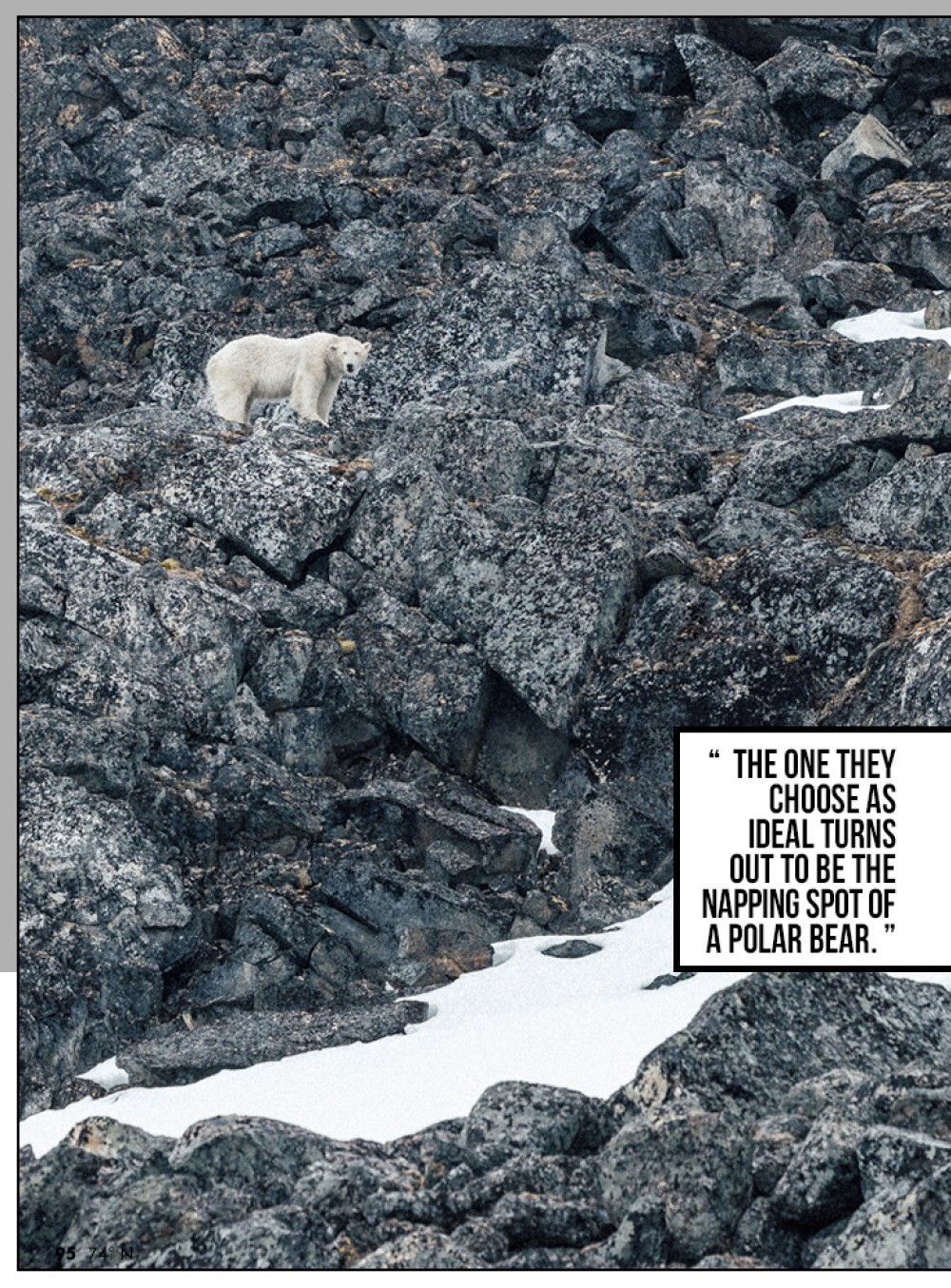

We are now anchored in a fjord that should get wind by the afternoon's end. Matt and Olivier check if there is a beach from which we can easily take off. The one they choose as ideal turns out to be the napping spot of a polar bear. Obviously, we decide to change spots and go for one a bit further away, without any land connection with the previous one.

Seeing their sparkling eyes, it's evident that observing a polar bear seems to be a unique experience. I'm so looking forward to it. Meanwhile, Olivier has spotted a perfect freestyle spot, a deep puddle inland where the wind seems to come in nicely. It's my time to shine.

It's been almost six months since I've done any unhooked freestyle, and I'm getting a bit nervous. I gear up inside the boat. Outside, the sky is grey. I think it's 11:00, but it's really 17:00. Freestyling in this cold is quite the ordeal, but Olivier is counting on me. This year, Maxime Chabloz is not here, so I'm the only one who can do these tricks for the video.

When I finally arrive on the beach, I discover a pool of fresh water surrounded by ice, perfectly in line with the wind. A dream. The only problem is that the temperature will not exceed 3°C. It's important to note that it is also impossible to put on neoprene boots and then fit into the freestyle boots. I must be barefoot.

I head to the water, and to my surprise, there are a bunch of walruses sleeping on the other side of this small lake. I don't feel like I'm disturbing them, so everything is fine. The cold pierces through the neoprene, and my feet and fingers are quickly numb. All my tricks are still there, and I land everything I planned to as if I were riding in Brazil at 25°C. Sure, it's nothing crazy and a lot of simple handle passes, but it's hard for me to do much more.

Olivier looks happy, especially with the alignment of my jumps with a vast glacier in the background. It's unlike anything we've seen before. I keep going for as long as I can. My feet have turned into two bricks and have been hurting for at least 20 minutes. I can almost feel the frostbite coming. However, and more importantly, I now remember how much I love freestyle, and how much I miss it.

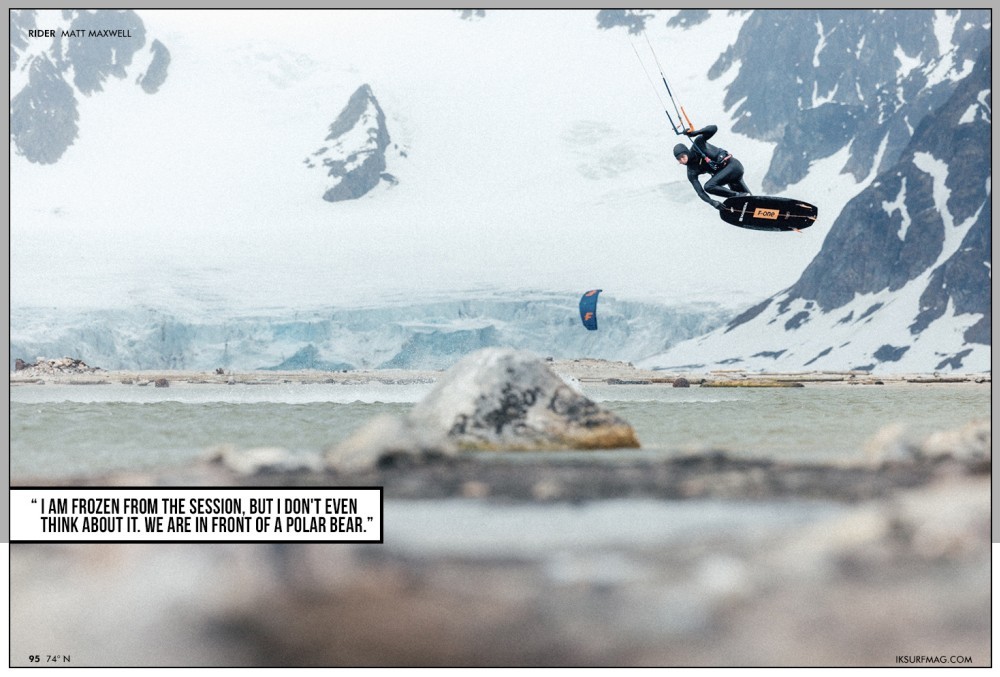

I signal to Olivier that I can't do anything more. He's not surprised, but tells me anyway, "That was totally stylish, man." Jean arrives with the dinghy, and we pack everything up. On the way back, Gaby warns us on the radio that the bear from earlier today is walking around nearby. We get as close as possible while keeping our distance so as not to disturb it. I am frozen from the session, but I don't even think about it. We are in front of a polar bear.

This animal is so mythical. I think back to all the books I read as a child and all the images and documentaries I've seen on it and its natural environment that is disappearing because of us and our actions. And then there is the present moment when we, humans, are face-to-face with it.

I have mixed feelings. On one hand, I feel guilty for seeing this bear, for being here. I feel like I'm looking at a living work of art that nature has created without permission. On the other hand, I see this living being staring at us and looking anything but unhappy. We must do everything to ensure that these bears do not disappear. Our generation and future generations must protect this more than anything else. Our children must be able to talk about polar bears in the present tense and not in the past.

That night, I hear the wind blowing incessantly through the halyards. I'm looking forward to doing Big Air here and Matt and Mallo even more. We return to the same spot as the day before and split into two groups. Initially, my role is to be on polar bear watch and to ensure they don't approach us or come too close. Tricks are landed one after the other as we are all enveloped by the cold and the dullness of this seemingly never-ending overcast weather. That said, I am under the impression that we are getting used to it.

No bears on the horizon. After more than an hour, I start to pump up my kite. The wind is not as strong as I thought, but it will do. The walruses are still there, unconcerned. They sometimes show their big teeth when we pass by. It is quite surprising, but I think they are just curious and a little startled to see humans gliding on the water. It must be said that they, and the polar bears, are the only wild animals that we have seen since our departure. This place is so extreme that even animals don't want to live here.

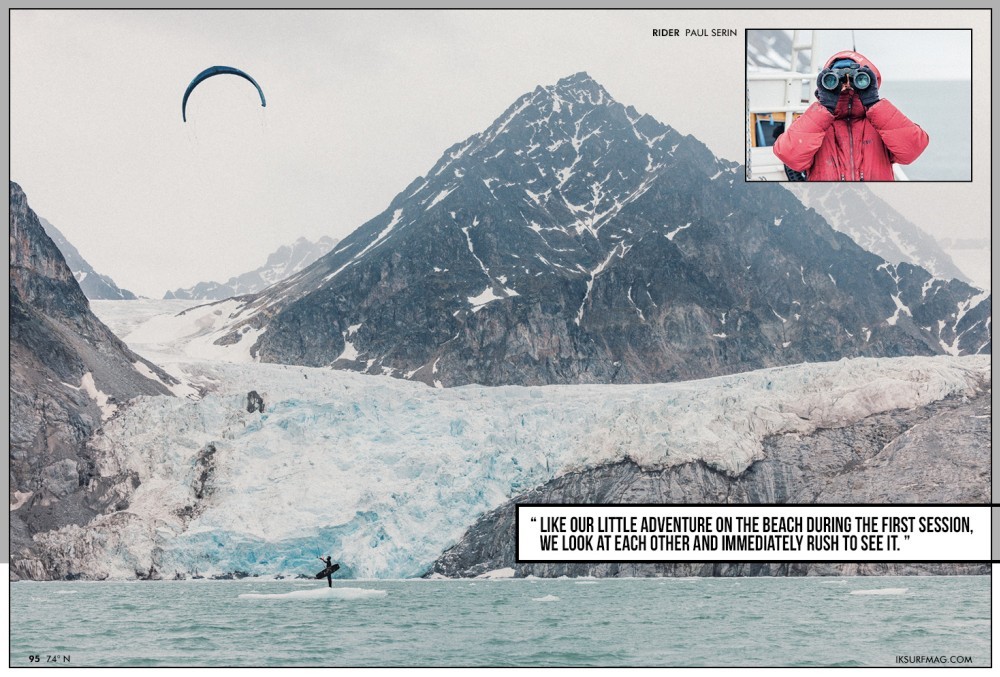

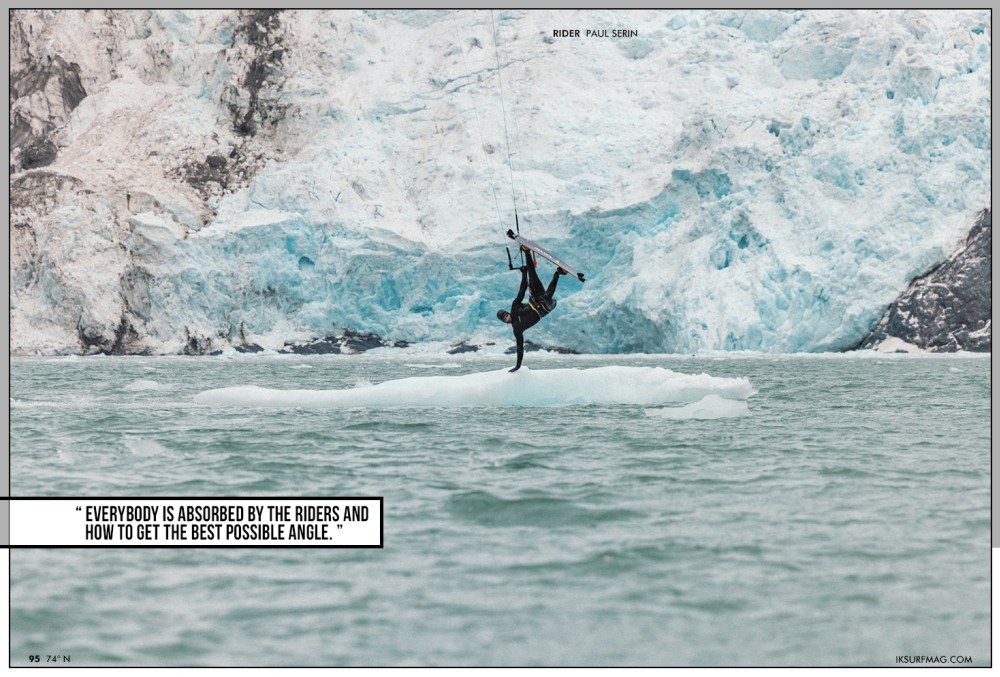

It's my turn to go in the water, but the wind is too light to jump high. With Mallo, we spot a drifting iceberg on the other side of the channel. Like our little adventure on the beach during the first session, we look at each other and immediately rush to see it. The drones get ready and follow us, but it is farther than we thought. If something goes wrong, it would be really complicated to come and get us. Everything will be fine, I tell myself several times.

When we finally get there, we discover a piece of ice of midnight blue colour and a much bigger size than anticipated. We are both a little impressed, but we still try a few tricks around it. Until a piece comes off, and the whole iceberg starts to rise. My heart races as I can already picture both of us stuck under it in frozen waters. A few minutes later, it has visibly and thankfully stabilised. We do a few more small jumps but eventually decide to head back before it gets bad, or the wind drops.

By the time we return, the wind has picked up a few knots, and we continue riding for a little while longer. No one is watching out for bears anymore. Everybody is absorbed by the riders and how to get the best possible angle. Back on the boat, Gaby is not happy. According to him, we took too many risks. Julien is of the same opinion. In hindsight, it's true that the situation could have turned out badly. Everything, however, ended well, and that's the main thing.

Once lunch is over, we go back to the water to wing foil this time. To minimise the risks, we decide to stay around the boat. But the wind is coming straight from a 500-metre-high mountain, so it is certainly going to be interesting. I put on my second wetsuit, which is only half dry, and my gloves which are completely wet. Instantly, my fingertips freeze and they hurt before I even touch the water.

Mizo is so impressive. For a Brazilian who rides in shorts all year, he has a rather exceptional resistance to cold. With nothing left to lose, I jump in the water and get going. I pass by Matt, the photographer, and tell him: "Get ready quickly; I won't last long". I do a few jumps and moves in front of his camera, but sometimes the wind gusts rip the wing out of my hands. Other times, we find ourselves waiting for one to get up and go again. My energy level drops quickly, and I head back to the boat after 30 minutes, leaving Mizo alone on the water.

The feeling of getting rid of a 6mm wetsuit is incredible, but not as much as the smell of the pizzas that Minh is putting in the oven at that same moment. Tomorrow, we change spots, and we continue our adventure up north.

The wind has decided to take a small break. We use this opportunity to explore our surroundings and, we hope, to see bears. The VHF crackles: "Gaby for Fred, Gaby for Fred". We all listen closely. Three bears are walking on an island a bit further north, near a whale corpse. We are all super excited. Seeing one bear was already crazy, but three would be sensational. We layer up and go on deck to enjoy the view. The wind is absent, the sea glassy. There is not a sound, just the water on the boat's hull. It's good to have some peace and quiet, too.

Without binoculars, it is almost impossible to see the bears. Even though they are white, they blend in perfectly with the rocks and the remaining snow - just one more thing to keep in mind when we go kiting! The whale is indeed there, and so are the bears. We take turns with the binoculars to observe them. The legal distance is 300 metres, but with all the violations that have occurred recently, it will probably increase.

It is sometimes difficult for me to understand humans in certain situations. No one would like to have someone stand and stare a few feet away while they are eating. Bears wouldn't either. We can observe them from a distance, and that's already a lot. The two cubs are busy butchering the remains of the whale. Their mother watches them, lying between two rocks. They look so peaceful and without any worries in the world. We continue our way towards a glacier and leave them to their feast.

We hope that a breeze will appear so that we can ride a little. When we arrive at the anchorage, the wind is more than absent, but the landscape is hypnotising. This huge mass of ice has been carved in time. We all ask ourselves questions. Since when does it exist? Is it really melting? Mizo has his opinion on the topic. For him, everything is cyclical. Personally, I find it hard to believe. I am not a scientist, but all the measurements show that glaciers are indeed melting.

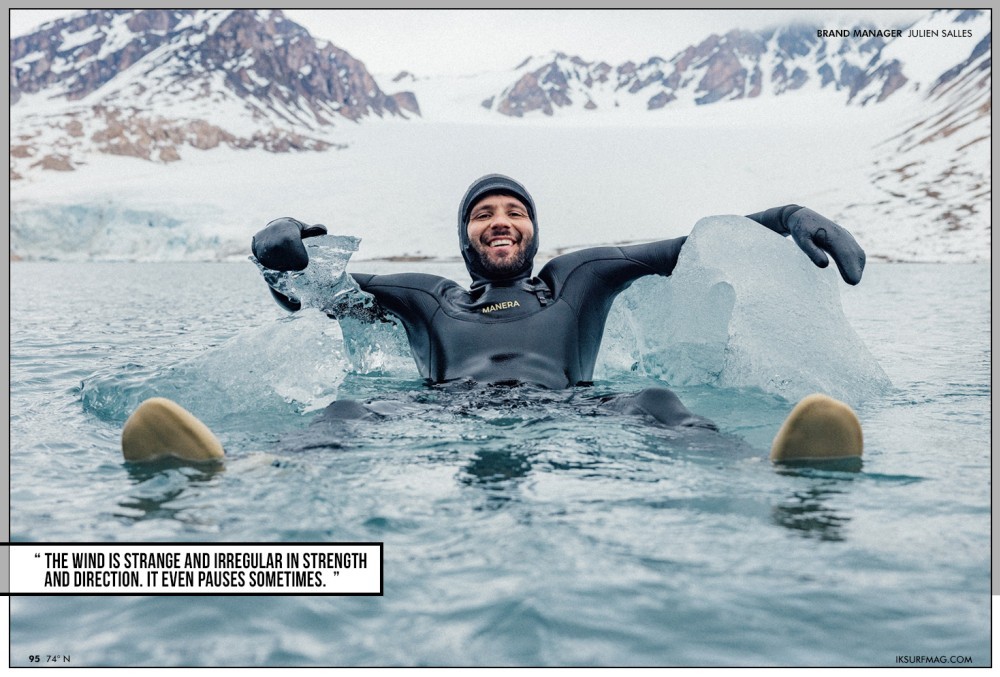

We gear up to foil around the drifting ice blocks. We take turns trying to do dock starts, but the wetsuit, gloves, and booties don't help at all. It's hard to feel anything with all this neoprene. We end up simply having fun on the ice, jumping in the water like kids, as if the water was actually warm when it was probably only 2°C.

We anchor behind a small island that should protect us in case of falling ice blocks. The noise when a piece comes off resembles a gunshot mixed with a cracking sound. It makes my blood run cold, even though it's already far from warm!

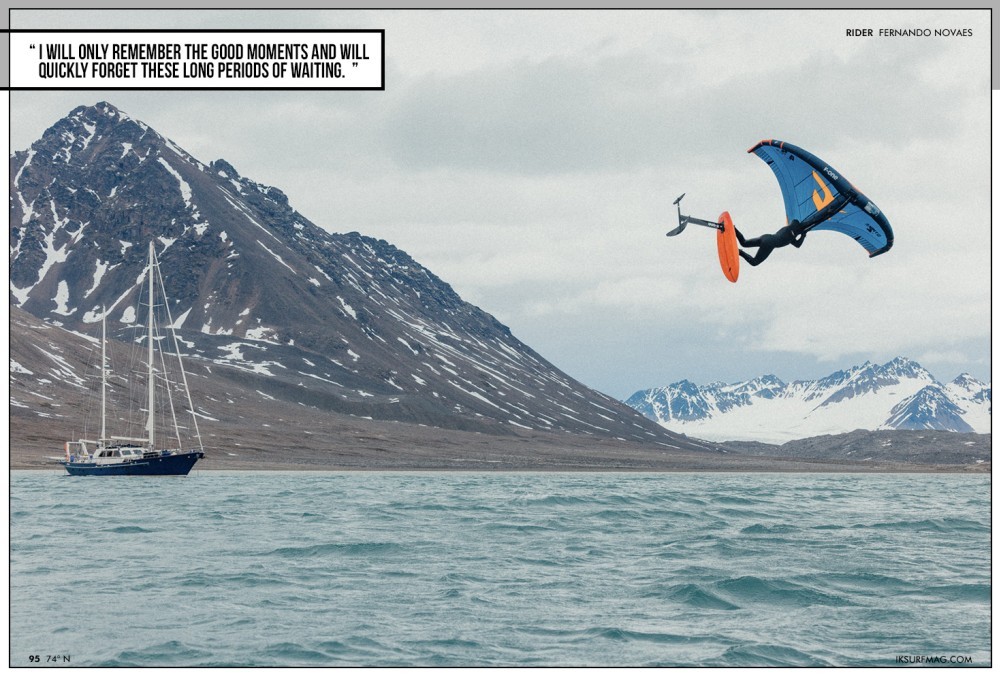

The following days are very slow-moving. Except for a walrus family that comes to visit us, nothing else happens. Waiting is part of the game; sometimes, it's hard to take. I put things into perspective and tell myself that once the trip is over, I will only remember the good moments and will quickly forget these long periods of waiting. I write these lines in my bed while the boat is not rocking too much. We have been on Kamak for a week now. Tomorrow, we start to head back south while, of course, looking for good riding conditions.

A gale is expected in a few days. Gaby is analysing all the options so that we can get to a rideable spot which is, at the same time, safe. It has got to be easier with skiers, that's for sure. But he likes the challenge, so I'm sure he's also enjoying this.

I get out of my bunk and discover that we have moved to a different glacier. We are in another bay, and there is wind! I rub my eyes to try to understand how it is possible that wind can blow directly from the glacier, but I don't think about it too much. I sense that Gaby does not want to stay here for a long time because of the ice and the bad weather.

I rush to put on my wetsuit and boots and go back on deck. Olivier and Matt are also ready quickly. I have the feeling that this is the session that can make this trip magical. Jean drops me off on a pebble beach to inflate my kite. He leaves me there alone because it is almost impossible for him to dock the dinghy with the swell caused by the falling ice blocks. It doesn't take me long to set my lines up, between the fear of bears, falling rocks and ice blocks, and other potential hazards I don't even want to think about.

Mizo joins me on the water. I don't even have time to tell him to watch out for the submerged ice blocks before he hits one and goes flying right in front of me. At least I don't have to worry about that on my twin tip. I feel one under my board from time to time, but it doesn't bother me much.

The wind is strange and irregular in strength and direction. It even pauses sometimes. I feel that Olivier and Matt are betting a lot on this session, so I give it my all. The glacier is behind my back. I can't really see it, but they can. Apparently, it's pretty insane. I do the best I can with the wind I have. After 30 minutes, I am frozen to the bone, but more importantly, I feel that the gusts are slowly decreasing in intensity. The end of the session is close.

I spot a small iceberg in the middle of the spot and jump on it to start packing my gear. I can finally turn around and see the glacier behind me. The blue of the ice is translucent in some places. The scene is unreal. I am standing on an iceberg, rolling my lines while a photographer and a cinematographer have their cameras pointed at me and this gigantic glacier in the background. I get back on the boat, and we quickly pull up the anchor to move to another bay.

Community life is sometimes a little heavy, especially between the crew and the riders. We want to go to places where Gaby doesn't necessarily want to go. But after all, it's his boat, so he has the final say. After yesterday's glacier session, we are anchored in a bay sheltered from the wind, but with a more bland landscape than we are used to. Julien and Olivier have asked several times if it could be possible to move, but the captain has categorically refused every time. We'll stay here. It's not bad anyways, and there is wind, so we can ride around the boat.

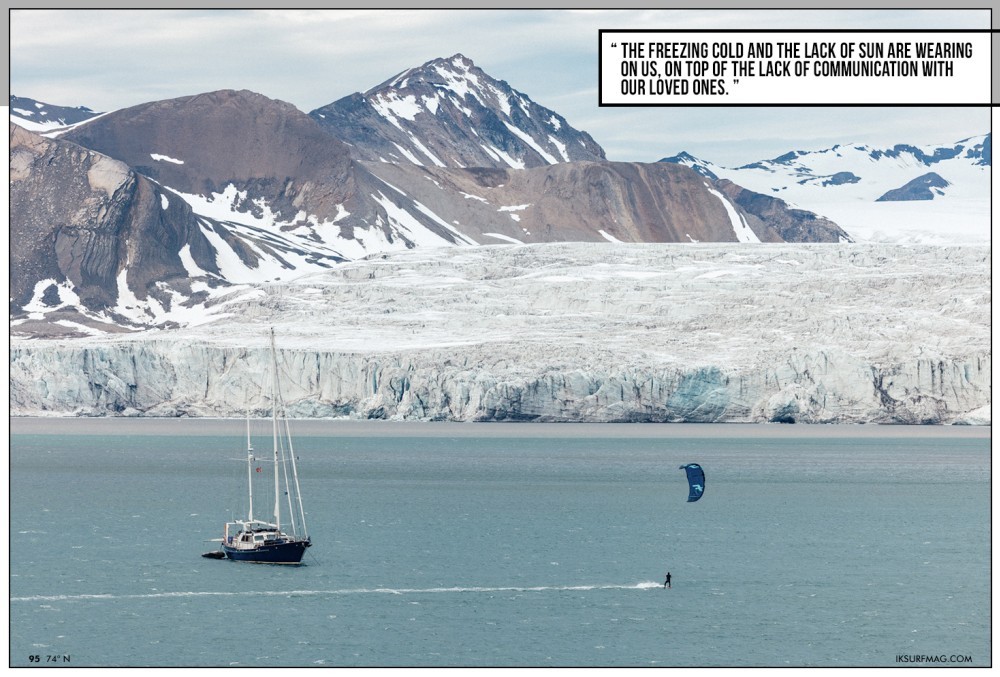

Everyone is able to get a session in: strapless for Matt, wing foil for Mizo and me, and a bit of twin tip for Mallo. We all feel fatigued. The freezing cold and the lack of sun are wearing on us, on top of the lack of communication with our loved ones. Moreover, I feel we are all a bit eager to head back, as daily life in this tight, cramped space is becoming difficult.

The following day, we start sailing at around 7:00. We continue moving south, but it will be rough, according to Gaby. I don't even think twice about it and take my seasickness pills. After more than 15 hours of sailing, the whole team feels alright and more than rested.

The phone signal is supposed to come back halfway through this sail, but it only comes back timidly, enough to let messages through but not enough to answer them. Deep down, I want it back, but only to talk to my loved ones, to tell them that I miss them and that everything is fine on Kamak. But, of course, a bunch of useless messages also come along. I decide not to open them right away. Mallo is like me. On the contrary, Mizo seems rather happy to receive all his messages.

The fjord where we anchor is perfect for sheltering us from the incoming storm. More than 35 knots are forecasted. The night is noisy. The halyards of the boat whistle loudly. Some gusts are so strong that I fear we will start dragging anchor.

At breakfast, we go over what we still need to shoot. Olivier really wants more freestyle. We get in the water with Mallo, him on a twin tip and me in my freestyle boots. From the boat, the spot looks cool. But once we get on the water, it is probably the worst wind I've ever ridden in, and I'm not the only one to say so. The air pockets and gusts are so abrupt that I find myself crashing on simple tricks.

Mallo is not comfortable either and eventually swaps his twin tip for his strapless board. Julien is up on a nearby hill on the lookout for bears while Mizo joins us with his wing. Almost all of us are in the water for this last session. After many attempts, I give up. I can already picture myself injured while having to sail back to the harbour in a massive swell for more than four or five hours.

In the afternoon, the wind speed doubles. It is impressive even from the boat, but Matt and I still try to do some Big Air. We are both a bit stressed. We see the gusts on the water, which sometimes create small tornadoes. Since we want to jump more than 10 metres high, it is not reassuring.

The wind ends up being exactly as we thought: horrible on all accounts. We try to give it our all, but we quickly decide to stop fighting against these awful conditions. The relief I experience when I land my kite is more than pleasant. Everyone knows the end of the trip is upon us.

That said, not much will be able to replace Minh's delicious meals after hours of riding. The last day is punctuated by a downwind next to the boat on wing foil, which I don't participate in, and a short cruise with all sails hoisted to reach our last anchorage point.

The sun is out again on this penultimate evening. Since the beginning of this trip, Olivier has been talking about going for a swim only in his swim trunks. It's now or never. He jumps first in the water, which again likely does not exceed 3°C. It's more or less bearable, but we only very quickly splash around like the real warriors we are!

After dinner, we lay down on the deck. The sun is shining brightly. It's midnight, but we all feel like it's noon. We discuss, put the world to rights, and enjoy these last moments near the North Pole of our dear planet Earth.

Reindeers leisurely walk around and look at us while grazing. Time seems to be frozen. Nobody wants to go to bed. I wonder how the people who live here adjust their biological clocks. Tomorrow, we return to port and civilisation. This civilisation that Gaby is desperately trying to escape by being here on Kamak, without any ties or mobile network. A life difficult to imagine for me and certainly for all of us.

After a short night, we are back at the port of Longyearbyen. It's thankfully a sunny day. We buy some souvenirs, drink coffee, and stroll along the only street of Longyearbyen. We run into tourists also on a last-minute shopping spree. We meet their eyes, but not for long. I feel like I just landed back on Earth after a trip to space.

We end up drinking beers on a terrace after the meal. The sun is as bright as ever, even though it's 1:00. I think about my family and my girlfriend. I would have loved for them to live a similar experience. Fortunately, Olivier and Matt captured it all. I can't wait for everyone to see what we saw.

The end of a trip is always filled with a lot of emotions, even though we have all wanted to go home at some point. Either way, we can't help but feel a bit blue when thinking about returning to our respective countries.

I've always loved to travel, to see the world, and to gain new perspectives. We are all modern-day globetrotters here. With our boardbags, we roam the world in search of new sensations, different conditions, or maybe even other things. No one really knows.

As Nicolas Bouvier says so well in his book The Way of the World: "After all, one travels in order for things to happen and change; otherwise, you might as well stay at home. Travelling outgrows its motives. It soon proves sufficient in itself. You think you are making a trip, but soon it is making you - or unmaking you."

That's exactly what we just experienced. It started with a trip and ended up being so much more. A human adventure, or a trip with friends in the Arctic Circle, call it what you want. In the end, it doesn't really matter. The important thing is to come back.

Gaby, Jean, and Minh will leave for another expedition while we will resume our normal lives. Our houses will be the same as when we left them, but we will return different.

Thank you, MANERA and Julien, for this interlude in our lives. It was magical.

By Matt Georges