Riding to Explore: An Alpine Expedition

Issue 92 / Thu 7th Apr, 2022

The climate is changing, glaciers are melting, and new lakes are continuously emerging. On an expedition that spanned the Alps, the Andes, and the Himalayas, Armelle Courtois and Martin Thomas are on a mission to highlight the effects of climate change. Read about their experiences kitesurfing in these incredible alpine environments right here in IKSURFMAG!

It was only recently that I found a love for the mountains, thanks to my brother, a mountain guide in the eastern Alps of France. He lives next to the Lac de Passy, a lake with a view of the south face of Mont-Blanc. I was visiting him on a windy day when he said, "It's kiting weather!". I always keep my kite gear in my car, so I replied, "Yes, why not try?!".

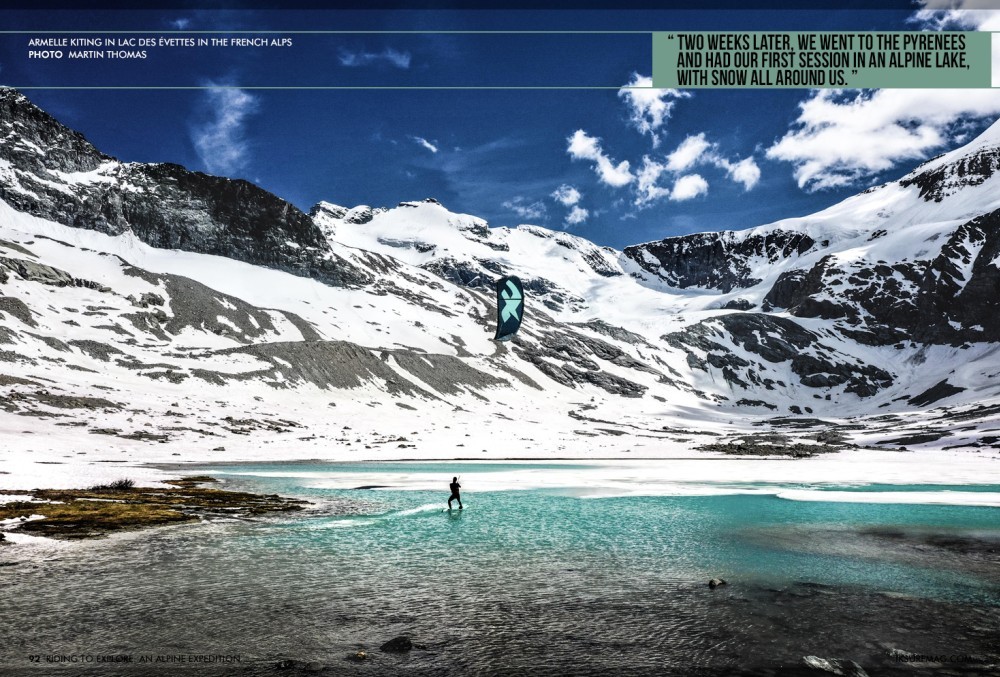

Kiting in a small, gusty lake surrounded by trees and rocks was not the most pleasant experience. But, riding in front of this majestic mountain was an incredible feeling. When I told my partner about it, he was thrilled, "We have to try this in the lakes in the mountains!" So, two weeks later, we went to the Pyrenees and had our first session in an alpine lake, with snow all around us. At this moment, we set our sights even higher, ready for an even greater challenge!

It was 2019 when Riding to Explore was created. I, Armelle Courtois, am a kitesurfer competing for speed records. My partner, Martin Thomas, is an avid kitesurfer and an Olympian, competing in Canoe Slalom. We set a goal to push the limits of kitesurfing and achieve an altitude world record. The plan was to journey to the Alps, the Andes, and the Himalayas, kiting in each location. But, almost as soon as our adventure began, our mission took a different focus.

The highest lakes come from meltwater from the glaciers, which has accelerated in recent years. We found lakes that did not exist just a few years ago. The rapid change in the high mountain ecosystems was painful to see. Once we became aware of it, we knew we had to push ourselves to see and share what was happening in the mountain ranges around the world.

We needed an experienced team to document the journey, particularly a director with an understanding of outdoor filming. In addition, they needed to be physically tough, with mobile equipment and the ability to handle an aquatic environment and cold climate. So we called Guillaume Broust, a specialist in climbing films. We also had the help of Christophe Tong Viet, who created our first short film, and Alex Lopez, who is working on the final feature film.

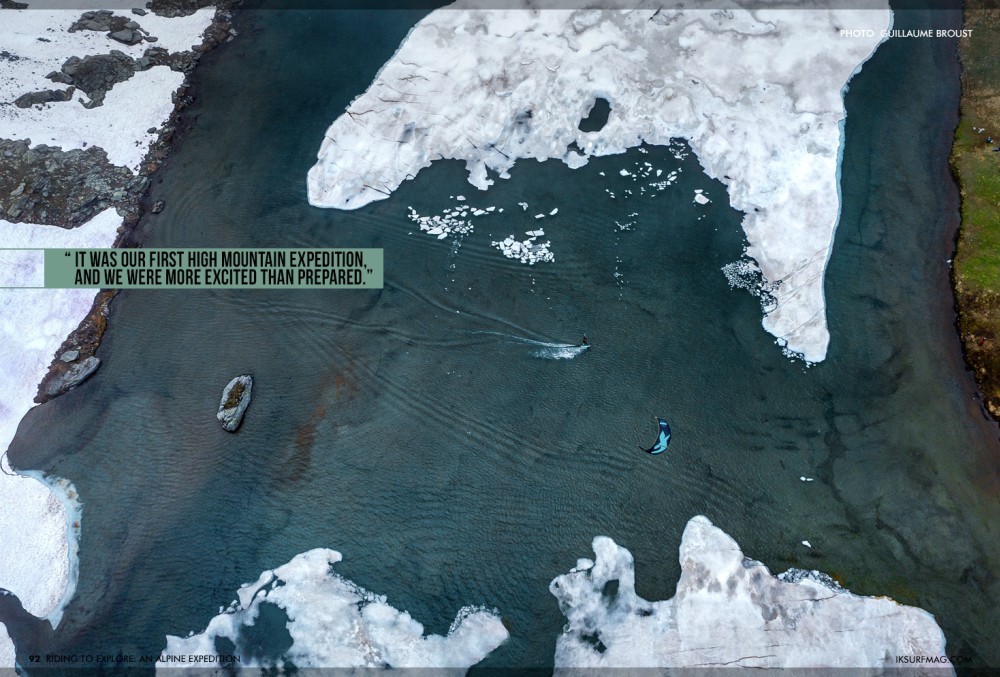

In the summer of 2020, our team set off on the first leg of our expedition in the Alps. It was our first high mountain expedition, and we were more excited than prepared. We only thought of kiting in the mountains and couldn't comprehend how challenging it would be. Each person had to carry 25 kg through rugged terrain; it was a long journey. We had to adapt, learning as we went along.

The alpine environment was, unsurprisingly, hostile for kiting. The launch areas were dangerously gusty, surrounded by high mountain faces, large trees, and sharp rocks. They posed a constant threat in the event of an error. To avoid hypothermia in the glacial lake waters, which were between 1° and 6°C, we had 5mm wetsuits complete with gloves, booties, a hood and a waterproof windbreaker jacket - an essential detail of a successful anti-cold combo! Most importantly, we had to plan a camp where we could manage the delicate moments after the session, when we had to quickly remove our wet clothes, completely exposed to the elements.

From Savoie to the Hautes-Alpes, there were five alpine lakes that we would attempt to ride. We had begun the trek to our first lake only a few days after lockdown had ended, and these lakes hadn't seen human feet in a very long time. The weather was bitterly cold, and we expected to arrive at a frozen lake. But, in the middle of the snow-covered surface, the lake was thawed, and the wind was blowing. It was an incredible start!

In the Northern Alps, our second attempt was thwarted by a frozen-over lake and worse weather on the way, so we headed to the Southern Alps for lucky number three. We arrived at a lake without snow and sunny skies. The wind, however, was nowhere to be seen. We bivouacked - stayed in a temporary tent camp - for two days and only managed to get one glorious hour of wind for the twin tip and hydrofoil.

Next, we continued to the Maurienne valley, finding our fourth, semi-frozen lake at an altitude of 2550m. We spent the afternoon floating in between icicles and icebergs, with not a whisper of wind, interrupted by short bursts blowing up to 20 knots, for just enough time to get up and ride! It was too cold and early in the season to find water any higher, so we returned home for a break.

In July, we hiked up to a lake at 2900m, just above the Grand Méan Glacier. We spent two days waiting for wind in the mountains in a stunning environment, with sun, rain, and hail. It is a sad fact that this lake is not listed on any map at the moment, as it has just formed. Launching a kite on the steep, rocky bank took some serious teamwork, but the final session was the perfect end to our time in the Alps.

Kiting in the high mountains requires precision and preparation. To be honest, we barely made it. Still, we knew we were doing something important and were determined to achieve our goal. Our expedition in the Alps allowed us to perfect our equipment, and now, we were ready to spread our wings and fly onwards to the Andes and the Himalayas.

We didn't know when we began, but the 3-month expedition we planned would take more than 2 1/2 years. Thanks to global travel restrictions, it was a year before we could reach Peru, but we were more prepared this time. We researched the effects of hypoxia, which is very hard to manage, especially while kiting. We also knew the high altitude would exert different pressure on the kites. On our way to higher peaks, we packed drysuits, essential not because of the cold water but the cold after the session and while we waited. We could conserve more energy by remaining in our drysuits the entire time.

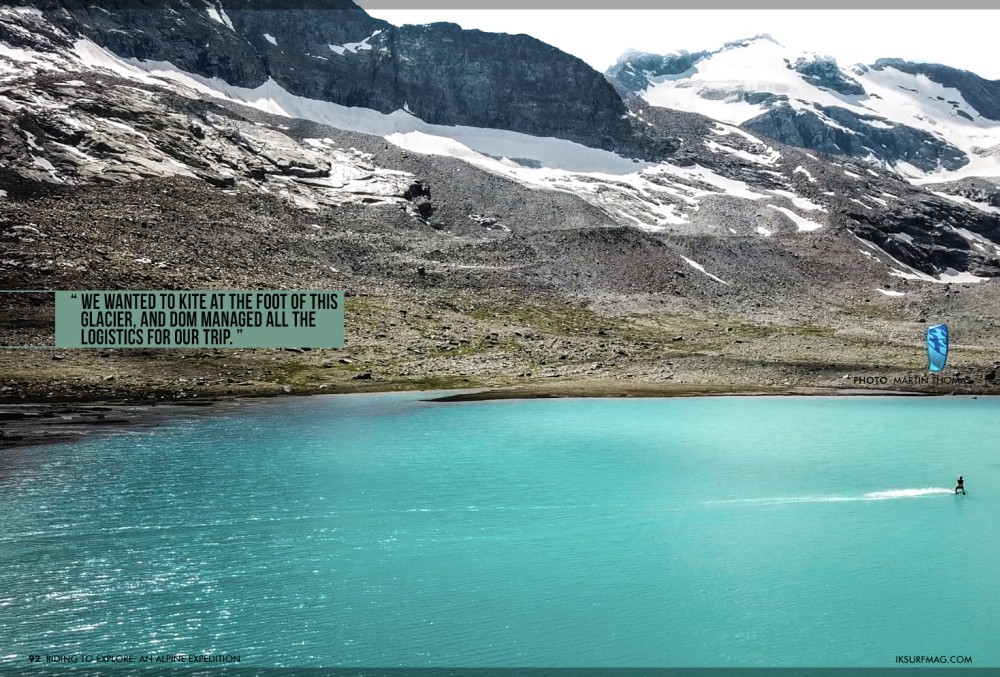

After reading his article on crossing the Andes with Stéphane Vallin, we reached out to Dominique Riva-Roveida. He knew the Quelccaya glacier, the largest tropical glacier on the planet. We wanted to kite at the foot of this glacier, and Dom managed all the logistics for our trip. In August 2021, we would finally meet!

Our French team - myself, Martin, and Alex Lopez - flew to Cusco to meet with Dom and the Peruvian crew before beginning the expedition. On the last evening before our trek, the cook and muleteers welcomed us into their home, in a small village at 4000m. They prepared a festive meal for their family and us, wearing traditional clothes. It was an honour and a truly magical way to begin this leg of our journey.

August is the month of the wind in Peru, though the predictability of the wind was in question. It was there, but sometimes asthmatic, always irregular, and turbulent in valleys dominated by summits up to 6000m. The sun would warm the day before the afternoon wind swept it away, resulting in a temperature drop from 15° to -10°C.

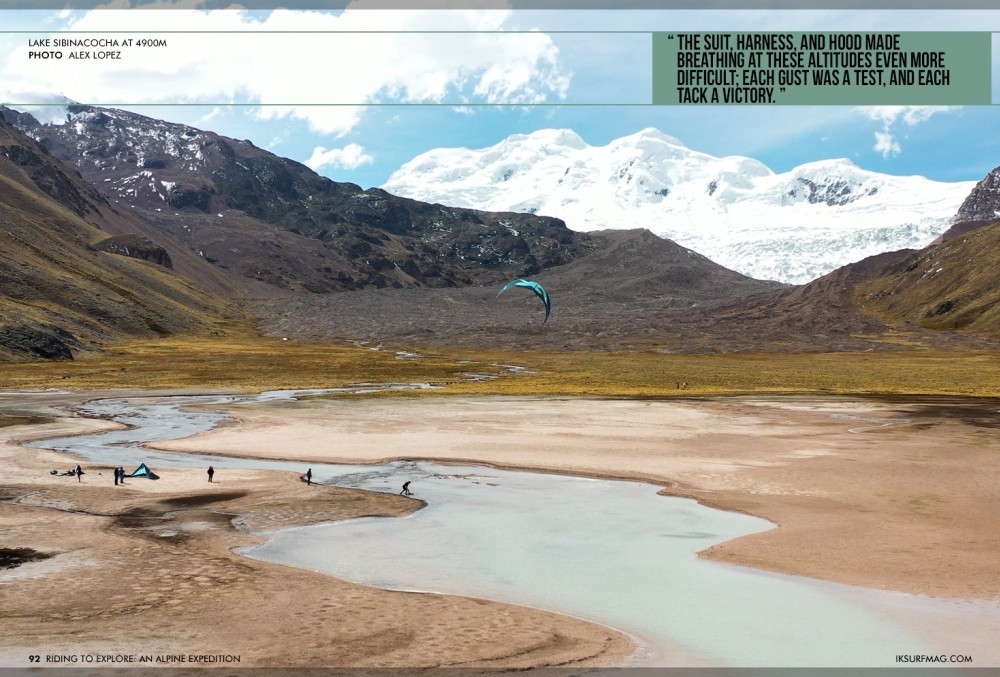

Every morning, at dawn, our caravan of ten horses, a guide, three muleteers, and the cook packed up camp and set off in search of a new lake, reachable in a half-day of steady walking. Despite the increased effort required by the altitude, the moderate rhythm allowed us to arrive in good enough shape to have energy left for a kite session. Every afternoon, with the kites ready, we waited impatiently for the breeze, looking up at the sky, watching for snow. As soon as the kite was in the air, the suit, harness, and hood made breathing at these altitudes even more difficult; each gust was a test, and each tack a victory.

At 5025m, we would face an intense challenge to achieve the world altitude record. It was a whole afternoon of battle, aborted launches, unsuccessful starts due to lack of power, a torn kite canopy, and confusion from hypoxia before we finally achieved it. It was an intense emotion kiting in front of the highest Andean glaciers, but we weren't finished yet.

Crossing the mountain pass at 5500m, we found another lake, sitting at 4900m. The weather was nice, there was wind, and we all felt relaxed after accomplishing our primary task. At the end of the 10-day expedition, we had ridden five out of six lakes attempted and achieved our kiting altitude record. In this amazing place with turquoise water, a glacier in the background, and pink flamingos, we soaked up the euphoria of the moment.

Peru is beautiful beyond belief, and the glaciers in the Cordillera are magnificent. Yet, more powerful than the physical achievement was the experience with our team. Muleteers are very kind, welcoming, friendly and happy people. They were dedicated and passionate about the cause of Riding to Explore. Together, we shared a unique human adventure.

We had achieved so much already, but the mission was far from complete. We had been planning the Himalayan leg for a year. Everything looked to be going well, but as soon as we got back from Peru, everything fell apart one month before leaving for the Himalayas. The pandemic halted tourism, visas were no longer available, and Sherpas were impossible to find - many were made unemployed by the agencies due to the lack of tourism. In short, it was a complete panic getting everything re-arranged in one month.

Unable to travel to Nepal due to travel bans, we found a way to the Himalayas via Ladakh, India. Fortunately, our film director Guillaume was already there. He had help from Dadul, a Ladakhi who set up his trekking agency there but also has a base in France. He put a great team at our disposal and managed to organise everything in two weeks. We got our business visas approved just four days before taking off!

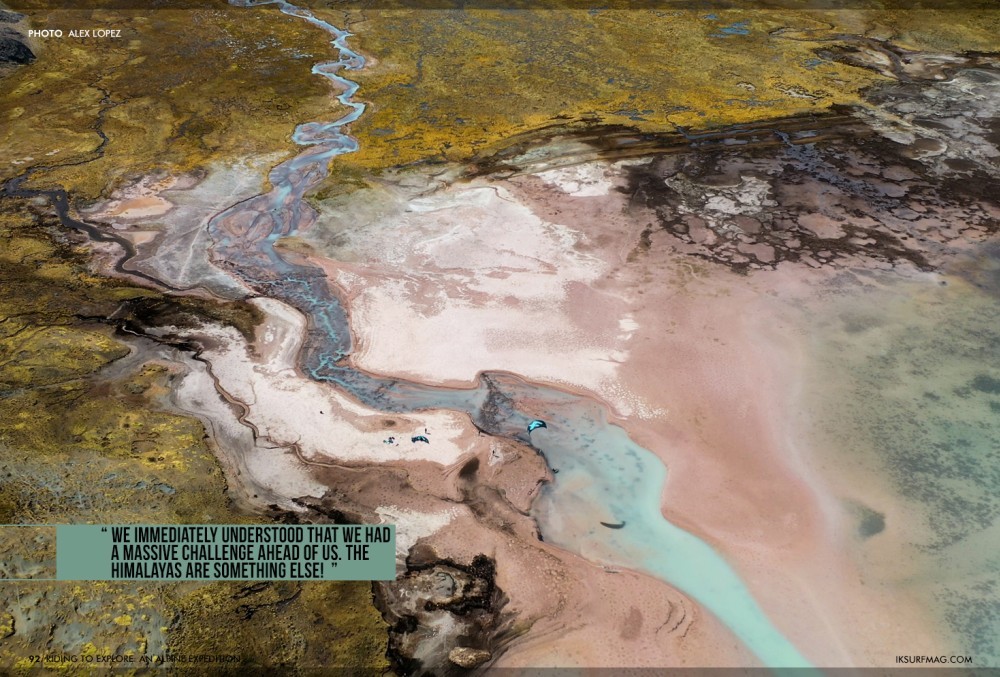

On October 16th, we arrived in the Himalayas. The country was still closed to tourism, so we were almost the only Westerners immersed in the local population. The Ladakh region is quite similar to Tibet; a great spirituality emerges from the monasteries perched on seemingly every mountainside. It is also a very militarised region because of its border with China. This duality between Buddhism, pacifism and militarisation was omnipresent and very contradictory.

In the highest and most beautiful mountain range in the world, we were in awe of the scenery around us. The walls are incredibly steep, with sharp ridges and vertical lines; it was striking. We immediately understood that we had a massive challenge ahead of us. The Himalayas are something else!

Each day, the team progressed in the middle of this rugged terrain, headed towards a lake located at 5400m. The locals told us it never snows until November, yet on October 15th, we were caught in a snowstorm with temperatures down to -30°. It was the fifth day, and we were at the advanced camp of the Nimaling Plateau, the lake only one day away. However, the whole team was blocked in at 5000m by the snowstorm. In 24 hours, temperatures plummeted, the ground and rivers froze almost instantly, the little vegetation burned, and snow obscured our tracks, with the wind blowing up to 100km/h.

It was over before it began. The lake had frozen and was no longer accessible, despite our attempts. Resigned, we descended the mountain. We needed to find the strength and motivation to go up another valley towards another pass, another lake that was less high, bigger, and salty, which would hopefully prevent it from freezing before our arrival. Regardless of the setback, we were more determined than ever to achieve our goal of kiting in the Himalayas.

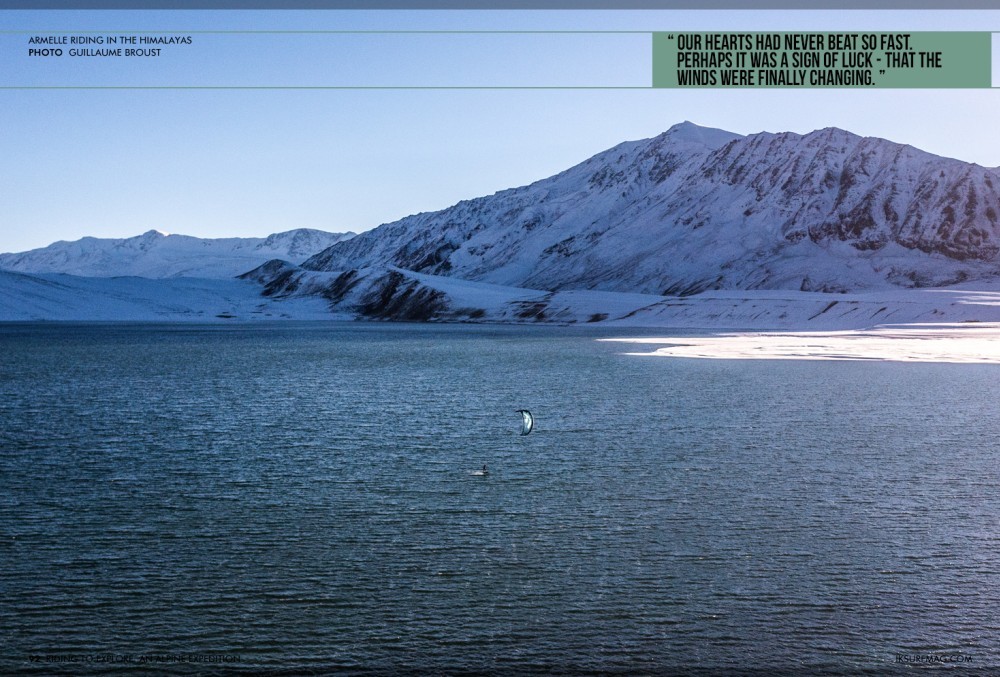

On our way to our new destination, I saw a slight movement on the cliff and immediately called out to the others,"There's a wolf, stop!" Look closer, we realised it was a snow leopard with two cubs - unthinkable! There was a river between us; maybe she had come to have a drink. She saw that we were looking at her. She watched us calmly, even sitting and laying down while keeping a curious eye trained on us. After 15 minutes, the leopard family continued their slow journey through the rocks. Our hearts had never beat so fast. Perhaps it was a sign of luck - that the winds were finally changing. To us, it was a gift from nature.

When we arrived at 4900m, we were relieved to find a well-defrosted lake and sunny skies, despite the -15°C ambient temperature! Unfortunately, the wind had disappeared in an area where it is usually omnipresent. We awaited its return for ten days. After six days of waiting, we arrived on the shores of Kyagar Tso, where the nomadic tribes that would typically occupy the area had left because of winter - all but one family. We explained why we were there, and they invited us to stay and set up camp next to them.

They welcomed us into their tent to warm up and drink tea with them. We didn't share meals; it would have been too risky for our small European stomachs to embark on kitchen tests. Despite the cold, the weather was lovely, and we enjoyed our days with the tribe outdoors. Their daughter Tanzin, a very independent three-year-old, spent all her time with us. She had unlimited, incredible energy, and we were sad to leave her.

After four days with the tribe, completing our ten days without wind, a wrinkled front finally formed at the bottom of the lake in the late afternoon. As it strengthened, the snow began to lift and swirl. There, surrounded by the world's highest peaks, in the enchanting Himalayan mountain range, we kitesurfed! For those 90 minutes on the water, all our past disillusionments flew away.

As our expedition drew to a close, we met inhabitants of the village of Gya. They had lost their houses when a section of the glacier fell into the lake, causing a devastating flood. Their testimony was a grim conclusion to our mission of discovery. Here, global warming is no longer a threat but a reality. Despite the seriousness of the subject, the last memory of this expedition will remain the smiles of the children, glowing on their faces while discovering the joys of flying a kite.

Everyone was moved by what we encountered in these mountain ranges. The rapid decline of the glaciers is immediately apparent in the Andes, and the floods in the Himalayas are directly linked to glaciers melting. In Europe, we often speak of climate change as a "threat" because we are not directly affected by it. Not yet. But in the places we visited, the people we met are already losing their homes; the springs are drying up, and the villages have to move because there is no more water. It is already happening.

We often believe that our small actions have no impact, but that's not true. We are the consumers; therefore, the industrialists follow what we validate by what we choose to consume. The first step is becoming aware of these issues and making conscious choices to combat them in our everyday lives. Let us all do what we can and not judge each other. Solidarity is the answer.

As kitesurfers who find so much joy in our natural environment, we see what we have to lose every session, on every trip to the water. Wonder, knowledge, and respect for nature is the best environmental protection. We must act now, later is too late.

Videos

By Armelle Courtois