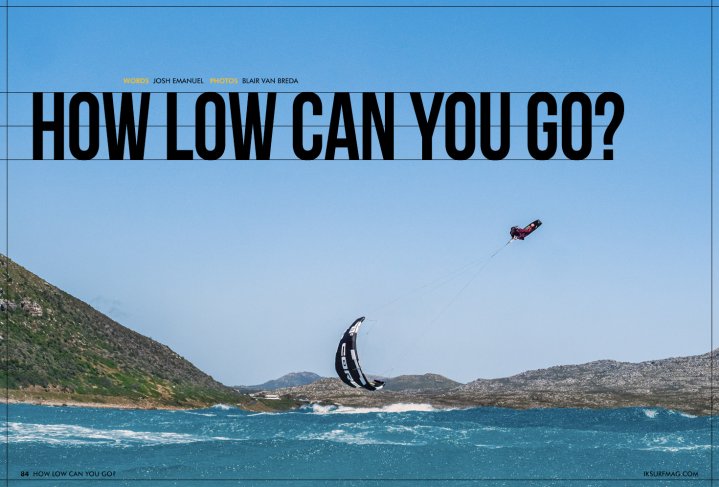

How Low Can You Go?

Issue 84 / Tue 8th Dec, 2020

When it comes to extreme big air, few can compare to megaloop master Josh Emanuel. The South African local continues to use his kite to challenge the laws of physics, looking for the limit of a low kite loop. Will he complete his quest to land the Infinity Loop? Find out in this article!

When it comes to extreme big air, few can compare to megaloop master Josh Emanuel. The South African local continues to use his kite to challenge the laws of physics, looking for the limit of a low kite loop. After years of analysing the paragliding Infinity Roll, Josh is ready to attempt the most extreme trick of his kiteboarding career: The Infinity Loop.

You know you’ve gone off the deep end when you lie awake at night asking yourself, “How low can I go?” Is it possible to get the kite directly below oneself and recover in time to make a safe landing?

This is a discussion that has been raging for years with Steven Akkersdijk, fellow Core team rider and megaloop addict. It always comes back to how hard we can push it, and how low we can truly go.

I’m speaking of the mythical ‘infinity roll’, a technique that comes from paragliding. A paraglider can perform an infinity roll by going into a spiral to generate enough speed to propel themselves into a complete roll, with the canopy beneath them.

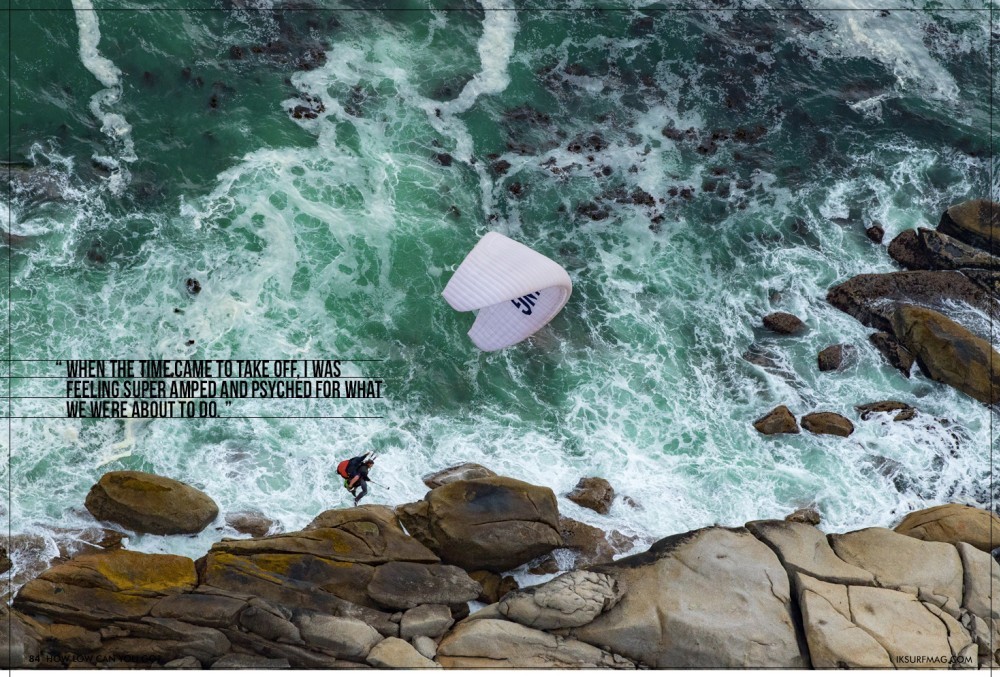

How does this apply to kiting? Theoretically, it’s a similar motion. At least, that’s what I thought until Zenti from Fly Cape Town Paragliding took me to perform this manoeuvre off of Lion’s Head. When the time came to take off, I was feeling super amped and psyched for what we were about to do. Except for one the one small fear I struggle with, which is heights!!! I know it sounds ridiculous as a big air kiteboarder, but yes, it is a fear of mine. Maybe this was the ideal time to confront that fear!

The take-off was smooth until we were about 20 metres from the cliffside and sailing at an elevation of 200 metres. My panic level continued to rise along with the elevation. I can honestly say that I haven’t been that scared in a very long time. I had the GoPro pole in one hand, while the other was gripping the strap as if my life depended on it. Zenti smacked my hand, saying through his laughter, “Why such white knuckles?” He continued to remind me to relax, explaining that the higher we go, the safer we are.

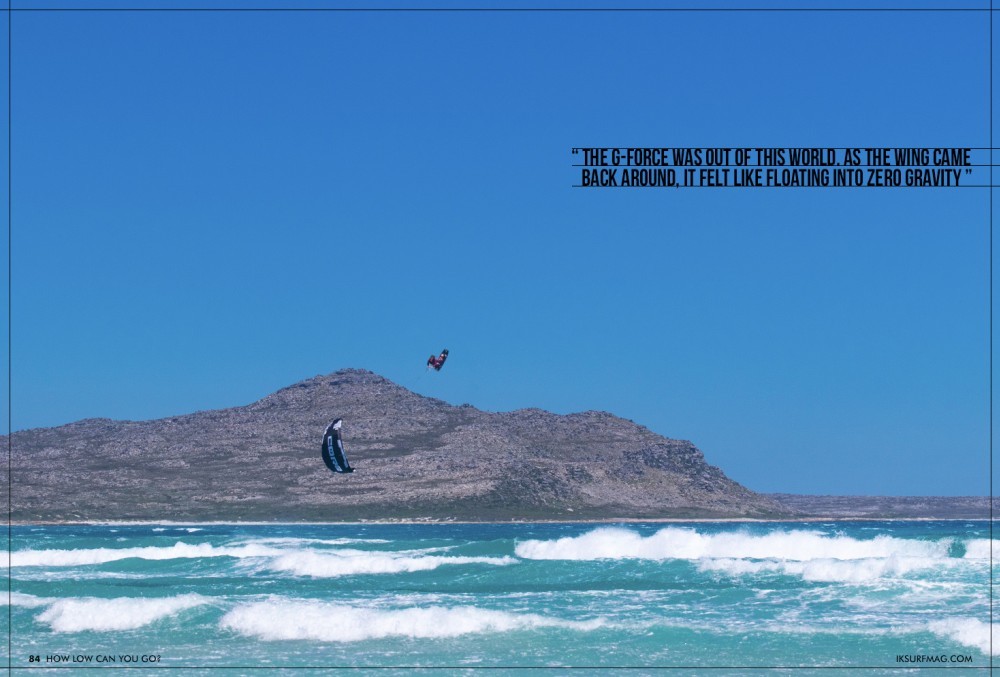

After about 10 minutes, we were floating 700 metres in the air. My fear had declined somewhat, and I began to enjoy the scenery as we glided out over the ocean. Zenti gave me a quick briefing about what was to come next: The infinity roll. We rocked left, then right. Before I knew it, I was looking straight down at Camps Bay, watching the world spin around me twice before we sent the loop. The G-force was out of this world. As the wing came back around, it felt like floating into zero gravity for a brief second before shifting back into forward flight once again. Never in kiteboarding have I felt the G-force that I did on the paraglider.

If you asked me before the flight if I thought these two things might be similar, I would have said an easy yes. Now, I’m not so sure. What I saw in the video compared to what I felt in the moment were completely different. With the kite, we steer it into the right spot and continue to steer to ensure we can stick the landing. On a smaller kite, our body acts more like an anchor that the kite pendulums around. With paragliding, I felt that we used our momentum to complete the loop. In a way, it felt even more connected than on the kite.

Perhaps a little background is in order. I had always loved the ocean, and board sports gave me the outlet to be able to play out there in the big blue sea. When I was 10 years old, I discovered that one of my friends from across the road had started kiteboarding. I had no idea what kiting was, and I had no idea what it would become to me.

For a few years, all my pre-teen self wanted to do was kite! I practised at every opportunity but had to take a few years off while in boarding school. The pull of kiting never went away. As soon as the opportunity came up again in 2009, I dove in headfirst. By 2010, I was ready to start pulling my first kiteloops at Sterkfontein Dam, a few hours away from my hometown of Durban.

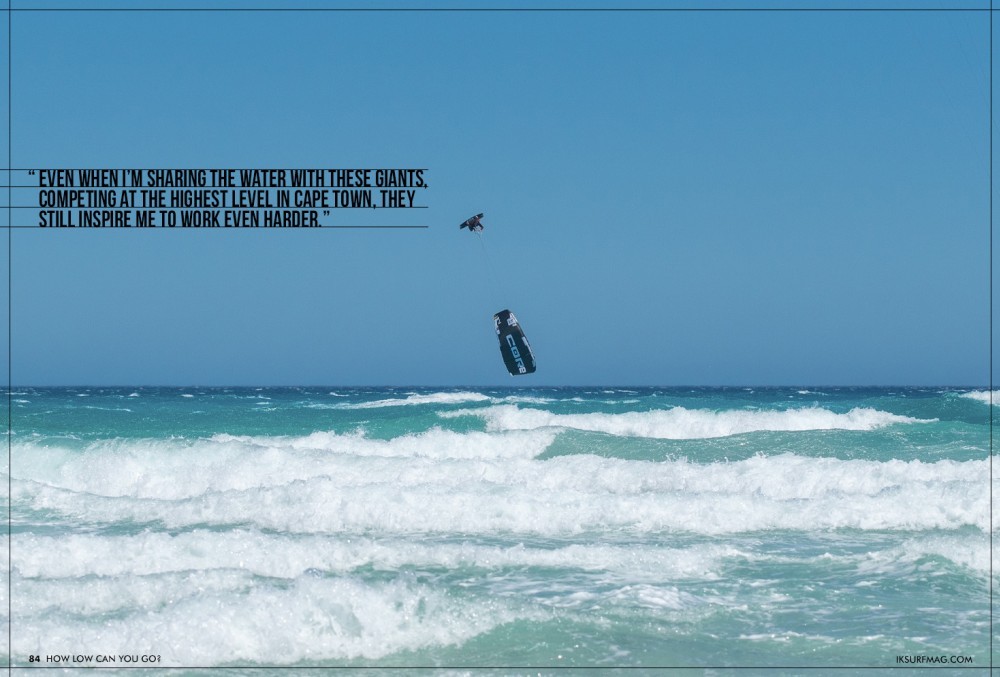

Watching riders like Nick Jacobsen and Ruben Lenten fuelled the fire. As a teenager, I kept pushing myself to try more and more extreme tricks, hoping to one day ride with these legends. Even when I’m sharing the water with these giants, competing at the highest level in Cape Town, they still inspire me to work even harder.

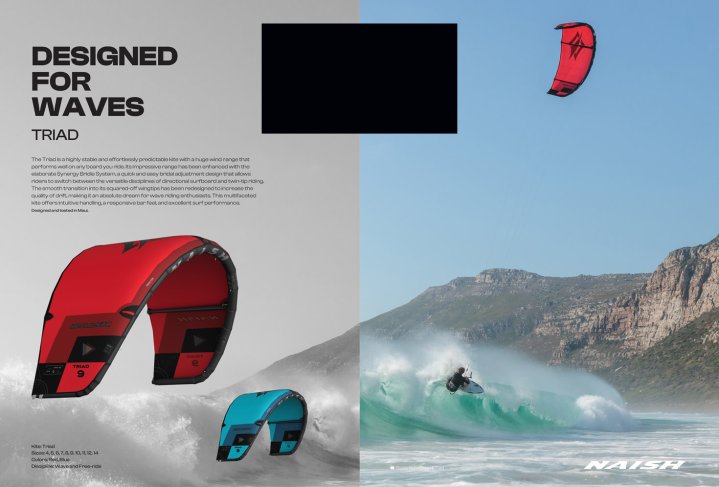

Now that I’ve been kiteboarding for nearly 15 years, I feel like I have both the experience and the equipment I need to take extreme big air to a higher level while getting the kite as low as humanly possible. With the design and technology at Core advancing so much, I felt ready to put the gear to the ultimate test.

Everything has to come together to create the ideal conditions to attempt the adapted infinity roll, which we in the kiting community have dubbed, the “Infinity Loop.” There is a lot to consider before even leaving the beach.

Strength of wind: As I have always said, “the stronger the wind, the higher you go.” When performing this type of manoeuvre, the extra height is critical. There is an instant when the kite no longer pulls you up, but pulls you towards the water, before looping around to pull you back up again.

Size of the wave: A solid kicker plays a vital role in giving me the height I need. Without that ramp to boost off of, the kite would hit the water at the bottom of the loop. If it clears the water, it wouldn’t recover in time for me to make a landing. A big, rolling wave would be ideal, allowing me more time to focus on where I need to steer the kite to get it lower.

Kite size: This can be a tricky one because a smaller kite is desirable in high winds, but they also give less lift and time to recover from the jump. A small kite means that timing needs to be perfect, or it can end very badly.

Length of lines: Megaloops can only get so extreme on standard equipment. I have been experimenting with various line lengths in the past few years, from 14 metres down to 6 metres. Once again, wind strength and wave size play a role in choosing the ideal line length. I don’t have this one down to a science yet. At this stage, it’s all trial and error. - and some errors are more painful than others!

Photographer: Finding someone willing to swim out and float around in the crash zone with a camera is a challenge in and of itself. Finding the right someone who can also handle the wind and waves, deal with water on the lens, and still somehow be in the right position at the magic moment? Even harder. Fortunately, I’ve teamed up with Blair Van Breda on several shoots, and I know he’s the guy to get the shot!

There was a week of wind in the forecast for South Africa, but the waves were not looking too promising. Still being a little early in the season, the winds have not reached their normal level of reliability. Nevertheless, we had to give it a go.

Our first attempt was at Kite Beach in Blouberg. It looked like the wind would come through at sunset, but the opposite happened. We found ourselves disappointed at the end of the day in the waning wind and light. We had to pack it in for the day and went back to the drawing board, desperate to make it happen before returning to Durban at the end of the year.

Looking further south to the village of Misty Cliffs, we found the wind blowing 30 knots, with the odd gust to 35 knots. It’s a bit on the weak side, but the combination of wind and rolling waves could get us close to that magical moment!

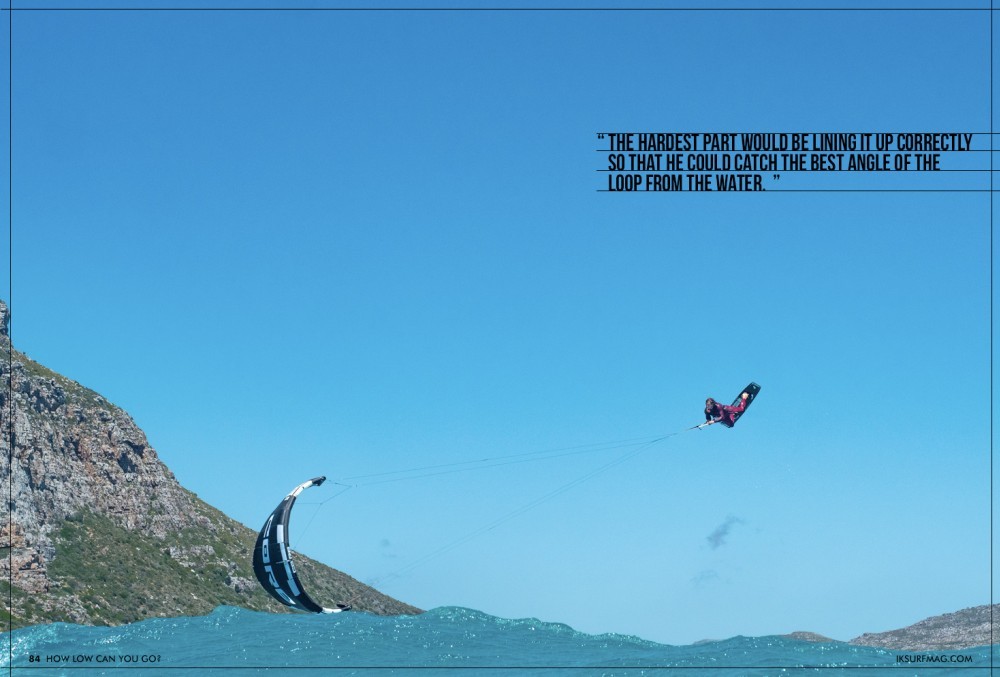

My first session was on a 7-metre kite with 10-metre lines. It was a struggle to get the small kite going, but it felt good in the gusts. With waves were on the small size, things were a bit more comfortable for Blair, who was in the water with the camera, but it was difficult for me to find a suitable wave to shoot off of to get the height I needed. The hardest part would be lining it up correctly so that he could catch the best angle of the loop from the water. There was an energy around the day, with Blair as excited as I was to capture the moment.

It is a nervous feeling, chasing that moment of weightlessness. I’ve always searched for the biggest storms and strongest winds. At 75 knots, it becomes one hell of a ride. It’s also where the biggest potential for downfall exists.

The rib injuries are the most painful. An hour drive to the hospital with a rib torn from the cartilage, and the feeling of a knife in the chest being twisted every few minutes is a hard memory to let go of. All I can do is swallow the fear, and keep moving forward. Sometimes I ask myself if it’s worth it. I know it is… If you love something, you will do anything for it. This is what I live for.

Funny enough, the conditions on this day weren’t anything to write home about. The kickers were super hard and every jump felt completely different. After trying several times, I was almost ready to give up.

There was a moment when I was in the air where everything started to line up. I pulled the trigger. There was a rush I had never felt before, like a volcano or an atomic bomb had just gone off inside of me. When I saw the kite start to recover, I started screaming my lungs out. I was still screaming when I landed. It was a rush I have never experienced before in my history of kiting.

I could see as I rode over to Blair that he was as elated as I was. It is impossible to put into words this feeling of joy and excitement. The noise of the wind and the waves and our shouts of triumph were deafening.

We headed to the beach together, eager to see the shot up close. Without the stress of moving water and strong wind, I could feel my heartbeat return to some semblance of normal. We were celebrating, jumping around in the shallow water like children. The shot was perfect.

There is something that happens when you do something so extreme. It must cause a massive injection of dopamine in the brain. It’s addictive, this feeling. I took 2 metres of line off of my bar and went back into the water, certain I could do better and get the kite even lower.

Less line length equals less power equals less height. Perhaps that was a calculation I should have checked before going back out in the throes of euphoria. I had built up so much confidence that I was ready to attempt this extreme low loop with a late rotation.

Against all sense, I went for it. Midway through the backroll rotation, I realised I had loaded the backroll too long and my kite was already exiting the loop. I went into an overspin, as did my kite.

I hit the water backwards, knocking the wind clean out of myself. I saw nothing but colours I didn’t even know existed for several seconds. As I started coming back to awareness, I was relieved to still be able to feel and move everything on my body.

Grabbing my board, I decided to stop tempting fate and head back to the beach. It was a wrap for the day. Time to celebrate an incredible moment captured of a manoeuvre that had never been done, as well as me walking away from another slammer of a crash.

That last impact was a reminder of how lucky I was. I want to mention this again: What I am doing is extremely dangerous, and has taken years of practice, dedication, and training.

People have asked me why I keep chasing the most extreme elements of kiteboarding. What do I get out of it? I do it for the love and passion I have for the sport. I believe that there is no ending to what you are doing. When you begin to think you are done, look at it from another perspective. You might realise that it’s not the end, but only the beginning. and you might realize that it’s just the start, not the end. What I get out of this is the joy of doing it and sharing my stoke with everyone else.

Today, I know I have pushed it further than anyone has before, but it’s not the end of the road. My last crash woke me up, not because I got hurt, but because I know I can go even further, train harder, and focus more to achieve what I have been dreaming of.

What's next? Well, simply to get the kite even lower.

Videos

By Joshua.Emmanuel