Is Kiteboarding Dangerous?

Issue 81 / Fri 12th Jun, 2020

Kiteboarding was deemed too dangerous and extreme to be allowed during the lockdown, so just how dangerous is it? Rou Chater dissects a recent study from some Dutch scientists exploring the injury rate in the sport. Is kiteboarding dangerous? Find out right here!

Is kiteboarding dangerous? It seems like a reasonable question given the recent sacrifices many kiters have made to help medical staff cope with the current COVID 19 crisis. Here in the UK, the mantra was: ‘stay home, protect the health service and save lives’. Dutifully we stopped kiting, it wasn’t banned (although driving to the beach was), but it was a collective effort by the community to become part of the solution and not part of the problem…

It does beg the question though, just how dangerous is kiting? After all, there are many sports out there that cause injury; you can get killed driving, crossing the road, choking on food in a restaurant. Toasters kill 700 people a year on average…that’s some number when you think about it.

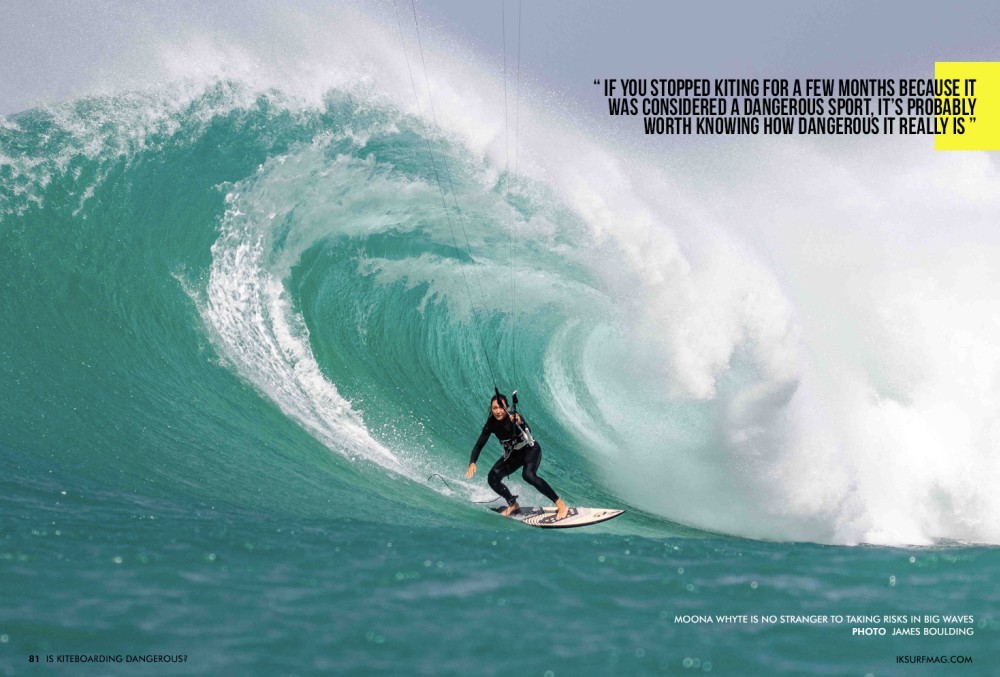

I won’t get into the rights and wrongs about various governmental approaches and the subsequent obedience or otherwise of the citizens. If you stopped kiting for a few months because it was considered a dangerous sport, it’s probably worth knowing how dangerous it really is.

Fortunately those kind Dutchies spent a year studying watersports and kitesurfing in particular to produce a study looking precisely at this question. You can see the full paper HERE, it’s typical thesis style fair, lots of facts and figures and data, and if you can get through the wording, it certainly makes for an interesting read.

From an outsider’s point of view kitesurfing certainly looks like a high-risk sport; I think the biggest question you get asked on the beach is if you need big muscles to hold the kite down - I doubt I’m alone in that. Equally, it looks like a pretty reckless past time to the average Joe on the beach.

I was there at the beginning, way back in the late ’90s and early 00’s when kitesurfing was in its infancy. The sport has changed immeasurably over the last 20 years. It’s quite incredible when you think about it. Back then the brands wouldn’t add safety gear to their equipment, as they didn’t want to get sued if it went wrong.

Fast forward 20 years and the brands have come together to approve a standardised safety system that has to meet specific requirements across the board. Thanks; mainly to the work of the GKA, the push-away safety system is being used by every brand out there.

In the early 2000’s, we had to build our own safety systems. Anyone who remembers spending a fortune on the Wichard QR Shackle and then modding a bar to give some semblance of “safety” in their back yard will know what I’m talking about. I’d regularly drive to the beach and in all honesty - and I mean this - wonder if I’d actually drive back or if I’d be dead.

When the wind came, kiteboarding was a serious business. The equipment lacked depower, control and the ability to handle massive shifts in the wind. Riders were getting slammed regularly, and even worse riders were dying too. It wasn’t until the mid-2000’s that things really started to change in the industry.

By the end of the ’00s, the sport had changed a lot, gear was safer, safety systems were emerging that worked, and bow style kites with wide wind ranges were the norm at the beach. In ten short years, the leap forwards in terms of safety was startling. Yet still, riders got slammed, and again kiters sadly died.

If you kitesurf and you are reading this then undoubtedly you know someone or have yourself been involved in some form of kitesurfing accident. It happens to the best of us; in a split second we can go from being totally safe to resembling a teabag getting dunked and bounced into whatever comes our way. Numerous friends have suffered life-changing injuries - I’ve had a few myself. It seems no matter how safe the brands make the sport, the element of danger is ever-present.

It’s easy to see why, when you think about the simple jump and the fact that most riders can boost 10m on command on a windy day. The physics of a kite are such that we are not heavy enough to hold it down. All we can do is use our technique and skill to keep the kite in places within the wind window where it won’t try and kill us, where we can control it.

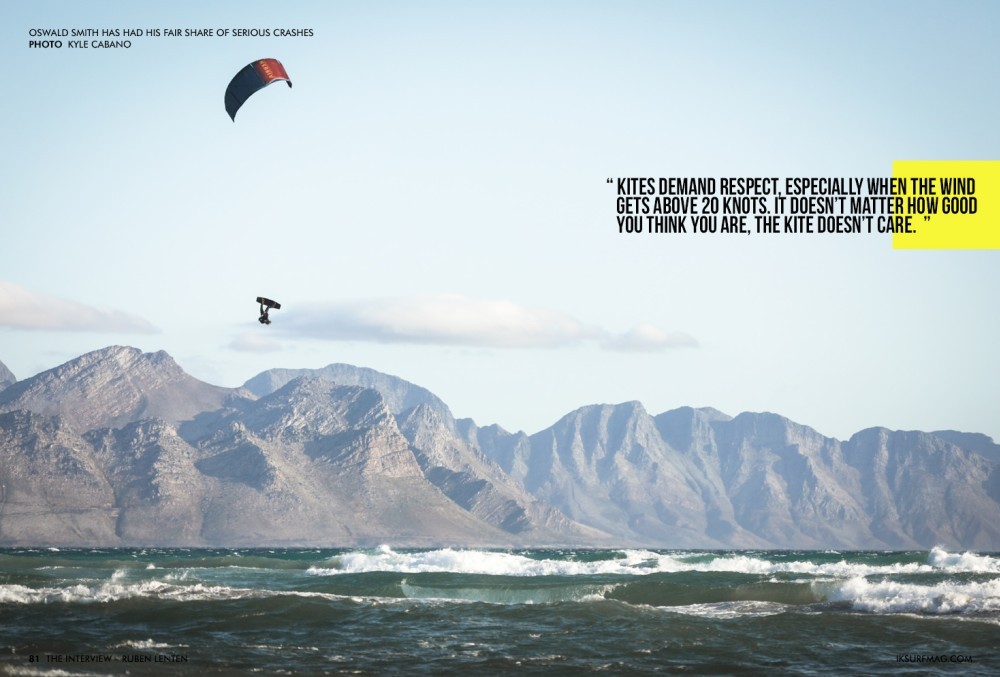

A freak gust, a lack of concentration, equipment failure are just a few of the factors that can put the kite somewhere we don’t want it to be in an instant, often with disastrous results. If you think you are immune to this, then you are foolhardy. Kites demand respect, especially when the wind gets above 20 knots. It doesn’t matter how good you think you are, the kite doesn’t care.

Injuries happen across a whole spectrum of riders: beginners, intermediates and experts, we are all at risk. That last word is probably the key to understanding all of this: RISK. As humans, we all have different aversion levels to risk. Women, by their nature, are usually more sensible than men (don’t jump down my throat on this, it’s a researched fact), and younger people are generally less sensible than older people. However, it goes much deeper and is typically rooted in personal experiences harboured deep in our consciousness.

When I was younger I really didn’t care, and that’s natural, it’s said that men don’t actually mature until they are 25. Before that their risk awareness is too low. This harks back to tribe mentality; after all hunting wild animals with a stick was a risky business. There’s a reason the “elders” stayed at home ready to cook whatever the younger hunters brought back.

This is why, tragically, it is usually younger people found buried in avalanche territory, a place where risk management is so critical it’s the difference between life and death. It’s a similar story with other pastimes too, motorbikes, cars, there is a reason why older people get cheaper insurance and women are often seen as a safer bet than young men. If the kitesurfing gear we use now is as safe as it has ever been, then it is down to how, and when, we choose to use it that matters.

For the study in Holland, the researchers worked with a group of 194 kitesurfers, both men and women, across a range of ages from 13-59. Over the course of the kitesurfing season from April to November, these riders logged an impressive 16,816 hours of water time. They were asked to record their time on the water and feedback any injuries they picked up to the research team.

A total of 177 injuries were sustained across the study resulting in an injury rate of 10.5 injuries per 1000 hours of kiting. The most common injuries were cuts and abrasions (25.4%), followed by contusions (19.8%), joint sprains (17.5%) and muscle sprains (10.2%). The foot and ankle was the most common site of injury (31.8%), followed by the knee (14.1%) and hand and wrist (10.2%). Most injuries were reported to occur during a trick or jump. Although the majority of injuries were mild, severe injuries like an anterior cruciate ligament tear, a lumbar spine fracture, a bimalleolar ankle fracture and an eardrum rupture were reported.

The conclusion of the study was this: “The injury rate of kitesurfing is in the range of other popular (contact) sports. Most injuries are relatively mild, although kitesurfing has the potential to cause serious injuries.” Which is, to be honest, what I was expecting before I read the study.

Kitesurfing has become so much safer in recent years it’s lost some of the drama of the early days. I certainly never drive to the beach, thinking I might not come back. I think I stopped doing that sometime in 2004. These days with massive wind ranges on kites and huge depower I feel reasonably safe even when it’s nuking. However, that isn’t to say we should be complacent.

As I mentioned earlier in the article, kites are ready to bite us in the ass at the first chance they get. Yes, they are tamer than in the days of old, but if you do the wrong thing with a 9m in 30 knots, you are always going to end up worse off. What’s really interesting about the study is that it dives really deep into the injuries and how and when they were sustained.

“The majority of the injuries were sustained in wind speeds of 4-6 Beaufort and flat to small wave (choppy) conditions, which are typical Dutch conditions. The vast majority (91.0%) of the injuries were sustained on the water. However, 49.2% of the injuries were sustained in shallow water, and 9% of the injuries were caused by an accident on the shore. Interestingly, all fractures were either sustained in shallow water or on the shore. Half of all of injuries were sustained attempting a jump or trick. In 15.8% of the injuries the athlete reported that lack of experience played a role in sustaining the injury. Loss of kite control was reported in 10.7% as a cause of the injury, and gear failure in 3.4%. In only 2.8%, the injury was caused by contact or collision with someone else on the water.”

“Most injuries were found amongst kitesurfers with 3-5 years of experience, but this was also the largest group of participants that reported the most hours of kitesurfing in the study period. A trend was observed for a decreasing injury rate with an increasing level of experience. Beginners with less than one year of experience had an injury rate of 17.5. With 3-5 years of experience the injury rate was 11.5, and this decreased to 7.8 injuries per 1000 h in participants with more than 10 years of experience. However, this did not reach statistical significance (OR = 2.23; 95%CI: 0.99-4.98; P = 0.052).”

The takeaway for me there is that nearly 50% of the injuries happened in shallow water or on the shore. Going back to the risk management aspect, it’s not rocket science to see that you can quickly make kitesurfing a lot safer. Don’t be a dick on the beach launching your kite the wrong way, not checking your lines, being too hasty to get on the water fast, etc., and don’t pull tricks in shallow water, where if you crash you are going to hit the deck.

Of course, the more risk-averse reader will say, well I can make kiting 100% safe by not kiting near the beach, not trying any tricks and just mowing the lawn. And you know what, that would probably work, but it would be pretty dull unless mowing the lawn is your idea of a great day out.

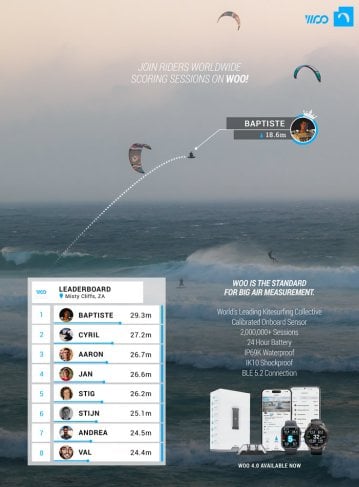

While the study looked at all aspects of kiting, it’s worth noting that the sessions were mostly held in the golden force 4-6 wind speed. This is where kitesurfing is at it’s most fun, without being overly dangerous. With the craze for big air and massive loops, the danger level increases exponentially. It’s how you kite, where you kite and when you kite that really matters.

Cruise the lagoon with a 12m kite going back and forth, and the chances of injury are slim. Turn the wind up a notch and start pulling some tricks and the danger level rises. Pump up in 50 knots with a mind-set ready for mega loops and the danger levels increase even more. It doesn’t matter how good you are at any stage of this, there is always a risk.

I’m far more relaxed on a 7m small wave day than I am when I’m clinging on to a 5m in a storm and chasing down monster waves. There is one last area of the study I want to touch on, the years of experience you have do mean the injury risk is lower. That makes sense, more experience is more knowledge and understanding of the risks involved.

A blissfully ignorant newbie is far more likely to pump up a 12m in 30 knots than the wizened old pro. Sadly with kiting we tend to have to learn the hard way. Nothing beats experience, but I’ve seen time and time again the kite doesn’t care about this, and when things go wrong it happens really fast.

To conclude, kitesurfing is safer than it has ever been, but it is a sport that carries plenty of inherent risks. It doesn’t matter how good you are, disaster can be lurking around any corner. Unless of course you wrap yourself up in body armour and mow the lawn with a 12m in 10-15 knots and don’t do any tricks. Let’s be honest, who on earth would want to do just that until the end of their days?! Be comfortable with your own level of risk, manage it and make sound decisions, the equipment is safer than it has ever been, but are you? Most importantly, never stop learning…

A special thanks to Christiaan JA van Bergen, Ginno MMJ Kerkhoffs, Rik IK Weber, Tim Kraal and Daniël Haverkamp for conducting arguably the most comprehensive study this sport has seen on the subject.

Videos

By Rou Chater

Rou has been kiting since the sports inception and has been working as an editor and tester for magazines since 2004. He started IKSURFMAG with his brother in 2006 and has tested hundreds of different kites and travelled all over the world to kitesurf. He's a walking encyclopedia of all things kite and is just as passionate about the sport today as he was when he first started!