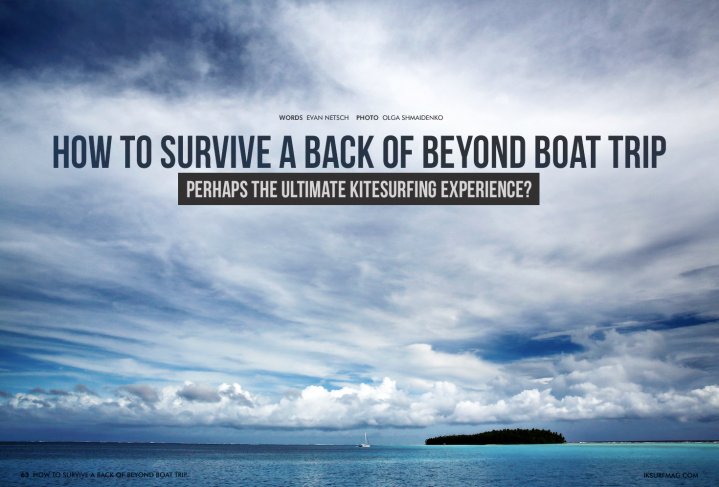

How To Survive A Back Of Beyond Boat Trip

Issue 63 / Wed 7th Jun, 2017

Evan Netsch heads off to the other side of the world on the Cabrinha Quest to ride in places where nobody has ridden before!

The pinnacle of any exploratory trip is being able to explore uncharted spots and lay claim to kiting in places where no one else has dared to tread. Evan Netsch was lucky enough to spend a bit of time aboard the Cabrinha Quest. In this feature, he gives us the low down on what he discovered…

The reality of any trip is that it’s always different than imagined. Seldom do I find myself in a place more amazing than what I expected, but this was one of those rare occasions. The biggest difference on this trip was the level of the unknown and the magnitude of the adventure.

Heading out into an area as untouched and remote as Micronesia was different than any other trip I’ve taken. We had to be totally self-dependent and we never really knew what we would find. First off, getting there was no easy task. Flying in from Hong Kong, I had to layover in Tokyo before landing in Guam, where I spent the night. The next morning I got on the island hopper, and after a few stops got off in Pohnpei.

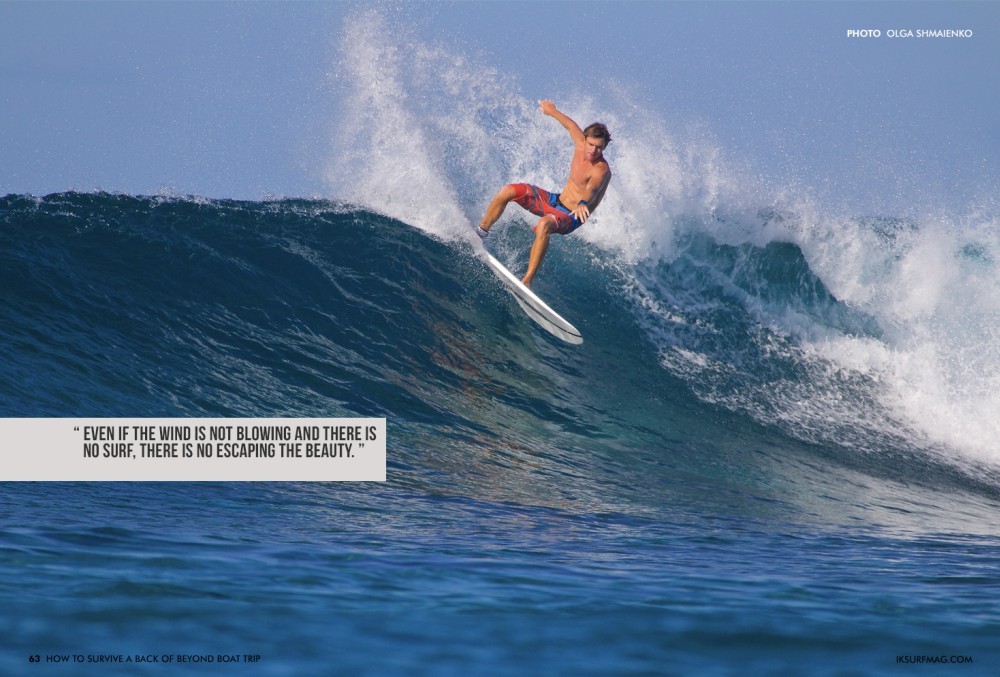

Flying in, the island looked dense and green, more like a rainforest than a tropical island, with the trees going right up to the water line with no beaches to be seen. Surrounding the entire island I could see barrier reef. As I looked out the aeroplane window, I could see a few different passes in the reef. One pass seemed to have an especially good right-hand wave. Being completely disoriented to where we were coming from and where on the island the airport was, I wondered to myself if this could be Palikir Pass. Or simply P-Pass, the wave I had dreamt of surfing but never imagined I would make it to. As it turns out, it was P-Pass.

The next day everyone has arrived. While Cabrinha sponsors the boat and, of course, Pete along with the rest of the team spend their fair share of time onboard, the boat is set up as a timeshare with all the owners eager to explore remote locations. In total there were ten of us on board. Tom and Emma take charge of the trip as the Captain, and First Mate, Lauren the Chief, Keith, Olga, Doctor Rob, Osh and Bowen were on board as shareholders, and I was helping out along the way.

After the boat had been provisioned, we headed out of Mangrove Cove where we were anchored. After about an hour sail we were out at Palikir Pass and not a minute was wasted getting into the water.

The surf wasn’t much more than head high, but the wave seemed perfect. The best part… we were the only ones in the water. This set the tone for the trip, sitting in the water as the sun was setting, toasty warm, with perfect waves and not a soul around. It could not have been a more perfect day.

For the next five days, we kited, surfed and explored all around the island of Pohnpei. The swell had been good for weeks, apparently, and we were just catching the tail end of it. After a day and a half, we moved to some other spots around the island to do some flat-water riding as the swell died off.

Not every day was windy, and when it was windy it was pretty light, but no one cared. When the kiting wasn’t good, there was never a dull moment. We swam with massive manta rays, snorkelled around the reef and WWII wreckage and even explored the indigenous ruins of Nan Madol from the 12th century.

After nearly a week in Pohnpei, we set sail for Ant Atoll. Only a few hours away, Ant is comprised of a couple of small islands, one of which is inhabited by just a few people. We spent a few days in Ant then we set sail for our next stop, Oroluk. This was a little over a 24-hour sail from Ant, so we left around 7 a.m. and sailed through the night, arriving in the middle of the next day.

We found different anchorages around the Oroluk Atoll, spending each day near a different little private island kiting, snorkelling, spearing food and enjoying the isolated setting. We sailed back outside of one of the atoll’s passes into the open ocean to do some fishing.

As we headed for the far side of the atoll, we planned on meeting up with a few locals who lived on the main island. As we re-entered the lagoon through the pass, the sky was overcast, and it was raining on and off, making dangerously shallow reef very hard to spot by eye. In the distance, we could see the little island, oval shaped and only a few hundred feet long at the most.

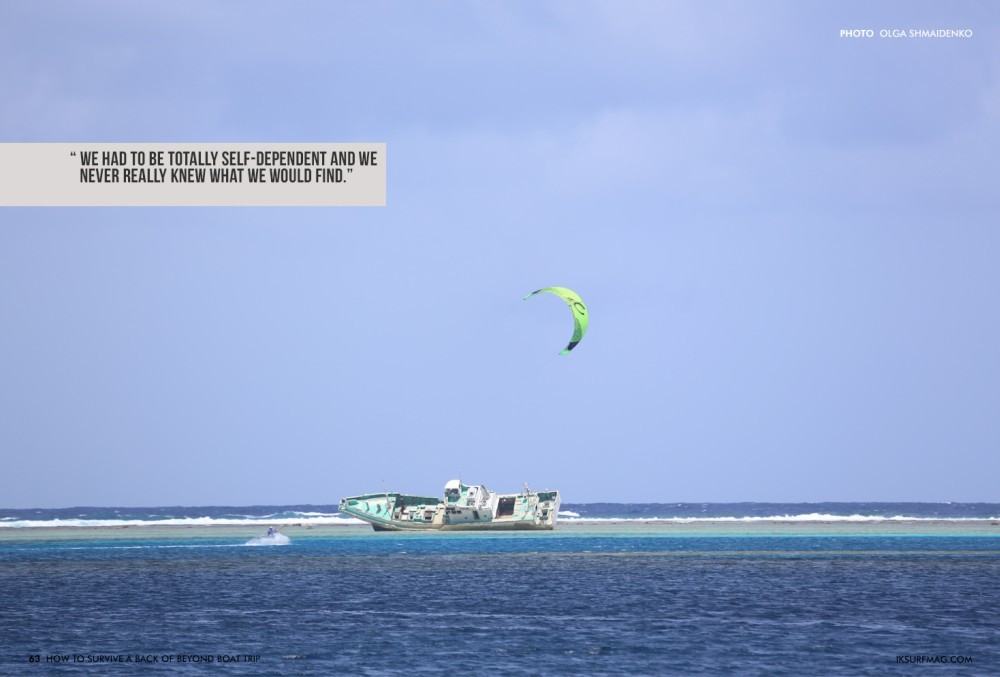

Near the island, we could see a small mono-hull wrecked. At about the same moment as we were following the charts into the reef pass, we realised that what was labelled as a safe pass was far from it. Waves were breaking everywhere onto the shallow reef, and the nearest pass seemed to be far in the distance.

At this point, we realised that our charts were totally useless. The area was clearly not navigated enough to justify creating accurate charts. We continued to carefully navigate in by eye, keeping a close watch on the water depth. We eventually came to a safe anchorage a mile or so from the little island. We now understood why the sailboat we spotted had become wrecked.

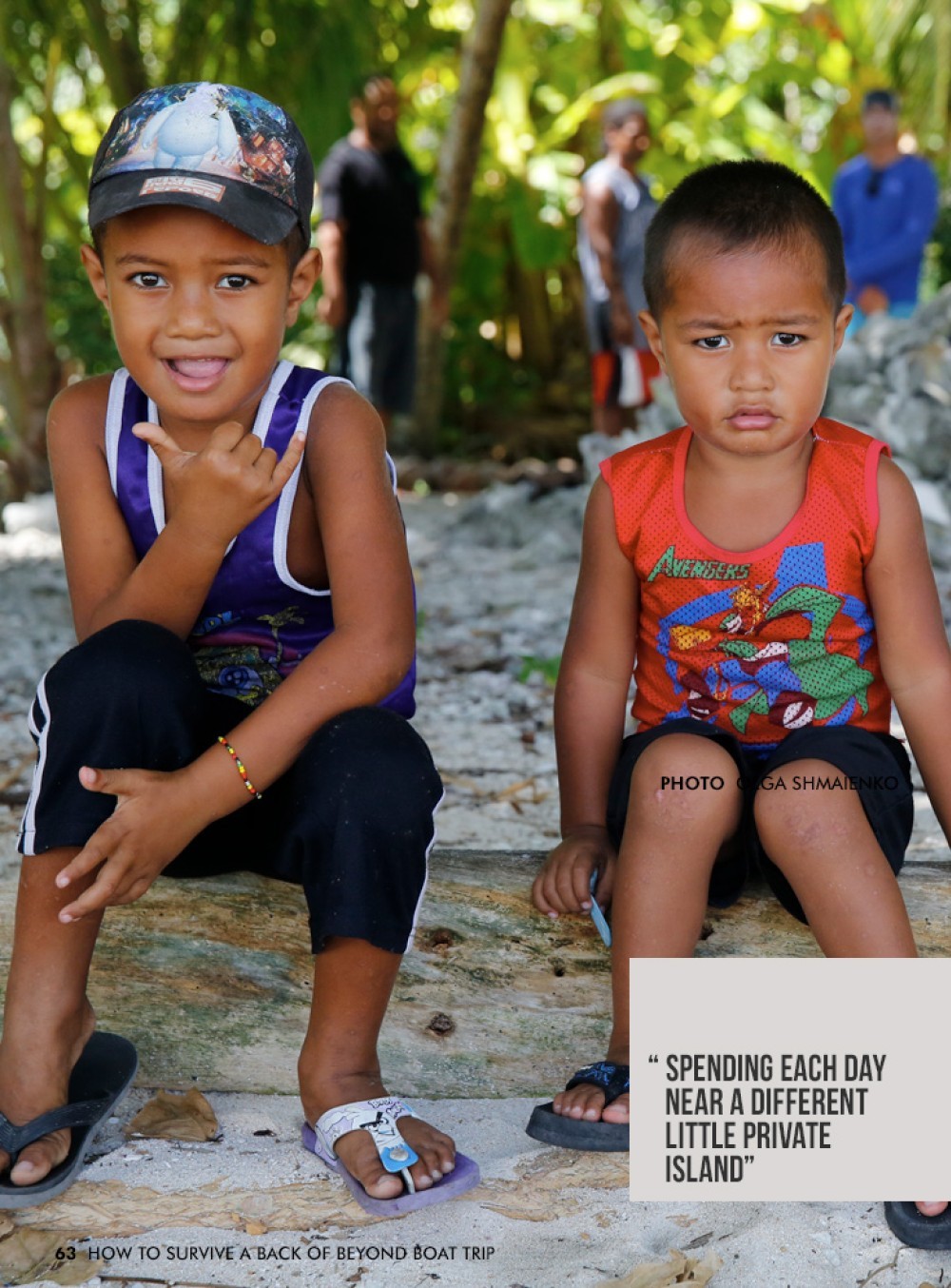

Meeting the Islanders was one of the most memorable experiences of my life. They live off the land, eating mainly coconuts, crabs, fish and rice that is supplied to them via US aid, either by airdrop or a from ship delivery every six months. One of my first questions to them was about the sailboat wreck, which was just offshore because it looked very recent. I was told that we were the first people to visit since the shipwreck, just over a year ago. At that, I realised just how far out there we had gotten. The seven people on the island had not seen another human in a year, and the last people who came were shipwrecked. To the islander’s fortune, they were now the proud new owners of a small solar panel and a wind turbine that they had stripped from the vessel, giving them power to periodically run a radio that allowed them to communicate with neighbouring islands.

Words can barely describe how simple their life on the island was. The only boat they had was about eight feet long, and it wasn’t much more than a raft with some makeshift paddles. Their homes were small, dirt-floor huts built from a mix of materials. Besides a pig and a few chickens, the only other company they had on the island was us, for the day.

After spending a majority of the day with the Islanders, we left them with some food, medicine for infections and a few colouring books for the three little kids. The next day, we set out for our final destination and departure point, Chuuk.

I’m not much of a sailor, which may be why the 32-hour sail seemed to take ages. Big seas and gale force winds made things pretty exciting. Wind speeds peaked in the pitch dark of the early morning hours with the sail at the third reef. Listening to dishes clanging and breaking in the cabinets all night long made it hard to get any sleep between watch shifts.

There’s no doubt it was an adventure, and I was grateful to have a skilled caption and first mate on board to keep everything under control. I’ve never been so excited to see the sunrise in the morning, knowing we would be making it to our destination within the day. As Chuuk approached in the distance, subsiding winds welcomed us to the island.

While all of Micronesia may be seen as one island group, the reality is that it is four, each distinctly different. Each island group even speaks a unique language, with English being the common language that allows them to all communicate. Chuuk was entirely different from Pohnpei, not only in landscape but also in culture.

The economic damage left in the wake of WWII was evident. A serious lack of work and high crime rates made us realise that this was not an area where we needed to hang out for too long. After spending nearly an entire day just clearing customs, we had little time left to explore.

The next day, we got back on the same island hopper flight and said goodbye to our friends onboard as they continued to sail south-west, bound for New Caledonia.

Pros and Cons

There are few places left in the world today that feel so undiscovered. Micronesia is one of the more remote areas left. While many of the islands suffered damage and are still healing their wounds from WWII, many are completely untouched. With over 600 islands, many of the outer atolls may not see a human for years at a time, and the ability to completely separate from the modern world is priceless.

The conditions are amazing, and options are endless. Many islands don’t offer the best surf breaks because the open ocean just lands right onto dry reef. However, there are a few semi-famous breaks like P-Pass, the dream right-hand barrel on Pohnpei.

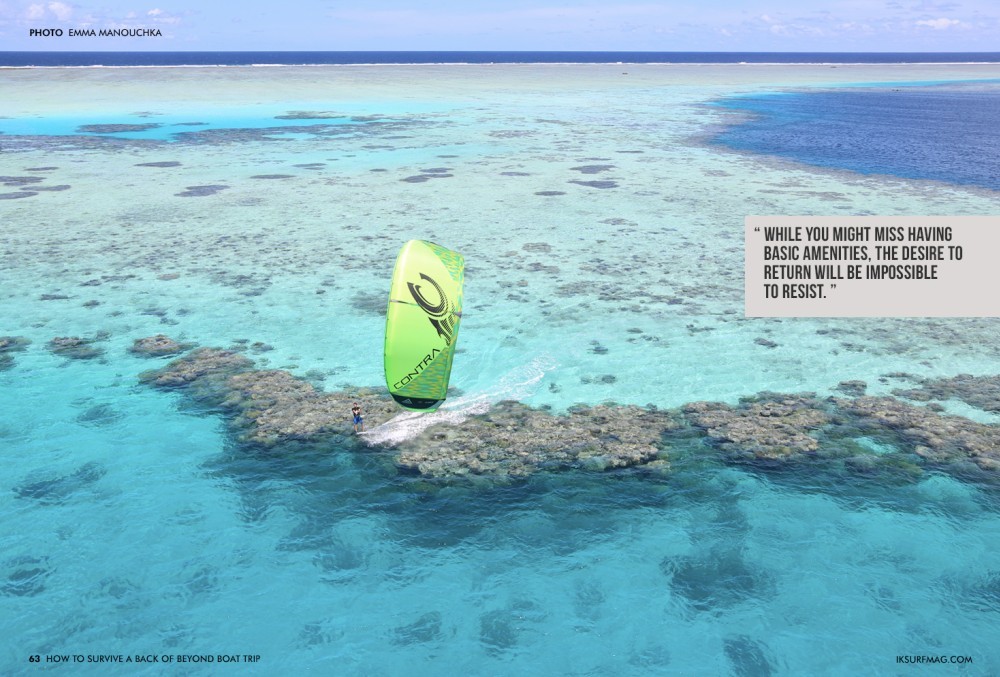

Adventurers who make their way to the outer atolls might be the first to kite or surf at many locations. We found this in Oroluk, about 125 miles west of Pohnpei, where our trip started. It’s an atoll surrounded by a barrier reef that offers endless, amazing flat water riding options, far from any civilisation.

It’s paradise. Even if the wind is not blowing and there is no surf, there is no escaping the beauty. With incredible reefs and remote islands to explore, there is no denying the natural, untouched beauty. With a long boat trip being the only way to access the area, it helped me to appreciate the surroundings without the interruption of modern day distractions.

These islands remain so untouched and remote because access is no easy task. It takes a day and a half travelling to arrive at any of the main islands in Micronesia, and to venture from there is nearly impossible. Without a live-aboard boat and captaining skills, getting to any of the outer atolls is not possible. This, in part, makes the islands so special, but there is no doubt, this is a limiting factor.

Micronesia is not a risk-free getaway. On any of the main islands, flights in and out are limited and so are general facilities. About midway through this trip, I broke a finger far from any hospital, and getting any sort of medical help was impossible. Ten days later, I was able to get an x-ray, revealing that I needed surgery and some screws. And, with a significant time lapse from the incident to the surgery, the healing process became much longer. A finger is only a finger, but it could have been much worse. With extremely limited medical help on the main islands and absolutely no facilities on the outer islands, we were reminded to be a little extra carful.

If you go to Micronesia, you will be spoiled. After surfing a perfect, open point break without anyone else in sight, or kiting from one unnamed beach to the next, it is hard to go back to a civilised reality. While you might miss having basic amenities, the desire to return will be impossible to resist. It was unlike any Caribbean island or topical paradise I had ever imagined.

Videos

By Evan Netsch