Riders On A Storm

Issue 62 / Sun 9th Apr, 2017

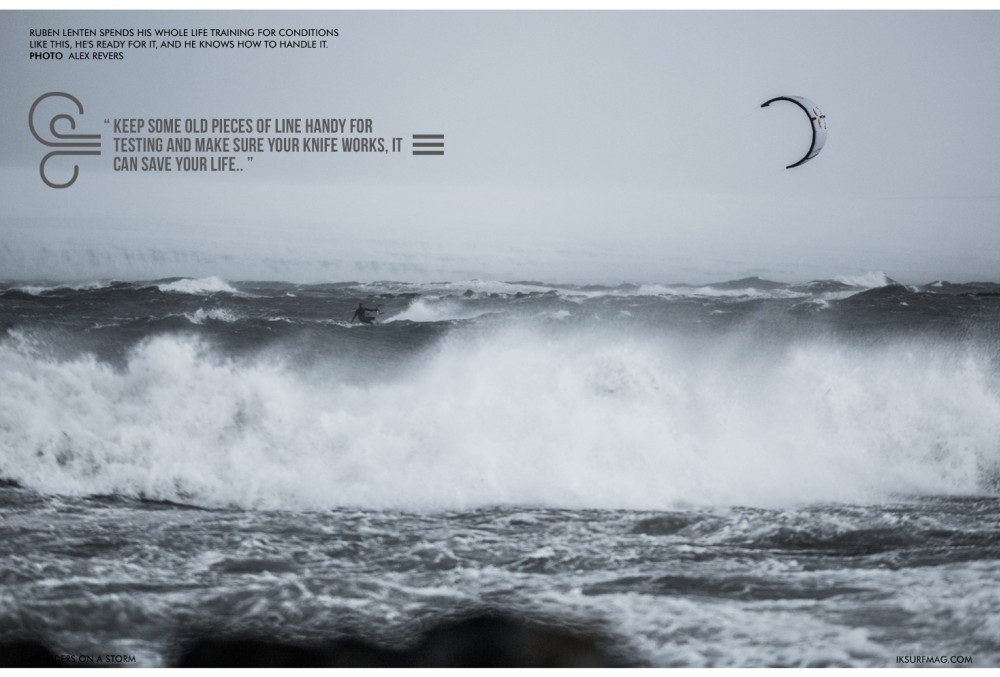

Rou Chater investigates the rising phenomena of kiting in stronger winds with bigger kites, the rising accidents and even deaths and looks at how we can protect ourselves and manage risk to stay safe.

Ruben Lenten, Steven Akkersdijk, Joshua Emanual and Lewis Crathern join Rou Chater in an in-depth study aimed at keeping you safe during challenging conditions and how to understand the wind and weather around you and manage risk.

There has been a definite shift in kitesurfing over recent years, with the development of better equipment, improved safety, and now devices that can track your jump height, more and more kiters are braving stronger winds, using larger kites and taking more risks.

This has led to a sharp increase in the number of kitesurfing related accidents and sadly even deaths in recent years. I’ve known a few of those affected, some have got away with a lucky escape and some light hospital treatment, others have not been so fortunate.

The fundamental issue here is that kitesurfing is relatively easy, anyone can go and buy a kite, and anyone can chuck it up in whatever wind they care to. Lessons these days are a two to three-day course teaching kiters how to fly kites and waterstart. Safety is a factor; however, often there is just a cursory nod to the wind and weather, which can be overlooked by students who just want to get on the water.

Equally a misunderstanding of how the weather truly works can be an issue for some. When the extent of your weather knowledge is looking to WindGuru and hunting out big numbers for your next big jump escapade, you need to take stock and learn a little more about what is going on.

On the flipside of the coin, a portion of the blame lands with us, the kite media. Big jumps and huge megaloops are huge pulls for traffic on our sites. Those GoPro mouth mount videos of massive jumps in Cape Town and elsewhere are click bait for the kitesurfing masses. Naturally riders see this and want to replicate it; after all, they have all the tools at their disposal to do just that!

The pro’s that we place upon that pedestal seemingly ooze talent and make it look so easy. In reality, those pro riders have spent years and years of training and knowledge building to get to that level. Your average weekend warrior is not putting in the same amount of graft before pumping up their kite during the next low pressure that rolls in. These days the best kiters are finely tuned athletes; they train day after day at the gym, on the water, building experience and strength that your everyday rider just doesn’t possess.

That same weekend warrior can pump up the same equipment in the same conditions and simply pull on one hand to induce a similar thrill ride. Whether they then have the skills to ride it out is another matter, in reality, it’s like being put in a Formula 1 car with a brick taped to your right foot, without any of the necessary skills to actually control what is going on.

A fundamental understanding of the weather is crucial in these situations. It’s no surprise that Cape Town, with it’s howling Cape Doctor blowing upwards of 40knots on a regular basis is the location for most of the records on devices like the Woo and the PIQ. It’s the place where all the pros go to train for big air in the winter and of course home to the event that showcases this extreme side of the sport, the Red Bull King Of The Air.

Why is Cape Town so popular and why does it have these accolades? It is because it enjoys a trade wind, not a frontal one.

A frontal wind is usually accompanied by stormy weather; we’ll get to those later, but first, let's explain trade and thermal winds a little more. This will help you understand why riders can jump 28m in Cape Town relatively safe in the knowledge of how the wind is going to behave while they are up there…

The South Easter or Cape Doctor blows during the summer months around the Western Cape; it is at it’s strongest around Cape Town, which is why Bloubergstrand has become such a hotspot for big air enthusiasts. The wind is created by two weather systems, the South Atlantic High-Pressure system and the Interior Trough Low-Pressure system over central southern Africa.

In the Southern Hemisphere, wind flows around a high-pressure system in an anti-clockwise direction, and flows clockwise around a low-pressure system. In the middle of these two systems sits the Western Cape and Cape Town itself. Due to the size of these two airflows, they join forces and flow in the same direction at this point, creating a strong trade wind. Winds of 100mph have been recorded in Table Bay due to this phenomenon.

On a hot day, the air temperature will rise over the land and allow the inversion layer to rise over Table Mountain, a height of 1000m. When this happens, the familiar “table cloth” appears, and the trade wind can blow unimpeded up and over the mountain and accelerate down the other side into Table Bay and the surrounding beaches.

If the temperature doesn’t push the inversion layer of the atmosphere up over the mountain, the wind cannot pass and instead flows around it causing light wind conditions in Table Bay. High winds can still be found at Cape Point where the wind is not impeded by Table Mountain.

Of course, this is the theory behind the Cape Doctor, and while it usually works in this pattern, there are exceptions to every rule. What I want to get across though is how this wind is created by thermal effects and an underlying trade wind which is created by a convergence of a high and low pressure.

Trade winds are predictable; they got their names from creating established trade routes. Before the days of engines, ships needed sails to get around, and as trade in spices and fine goods flowed from the East to the West trade routes were established using the prevailing winds, which soon became known as the trade winds.

A frontal or coastal wind, however, is very, very different. The chances are if you live in the Northern Hemisphere frontal winds and low-pressure systems are what drive your kitesurfing. During the summer months, there are locations that enjoy a sea breeze, where the land heats up and sucks in cooler air from the sea. Sea breezes again, are similar to trade winds and although often very localised, such as the one that blows on the South Coast of England around the Brighton area they are very predictable, usually reaching maximum speeds of around 25 knots. Perfectly safe for kitesurfing, however they only occur on hot sunny days, and so during the autumn and winter they are pretty much ruled out.

You’d be forgiven for looking at the pictures of pro riders heading out in 45knots in Cape Town with a 9m kite on a quest to smash their personal jump heights and each other and thinking you could replicate that at home. Especially when you see those deep purple numbers on WindGuru.

However, the conditions are fundamentally different and herein lays the rub.

Storm systems in the can be massive, and they move very quickly. In front of the system there may be some good winds blowing through, but as the system gets closer, those winds can sheer, shift and increase exponentially.

That last word is important too; wind is exponential. On a 10 knot day when a 15-knot gust hits you won’t feel too much, perhaps a good boost in power at the kite. However, on a 35-knot day, that same 5-knot gust can feel like you’ve been kicked in the back. Move up the scale even further to a 50-knot day and another 5-knot gust, and it’s enough to knock you clean off your feet. It’s the same 5 knots of wind, except its power has exponentially increased…

The higher the wind speed, the stronger the gusts are, and it’s those gusts that people often ignore when looking at the weather forecasts. Gusts are a hugely important area of the weather to check, 10 knot gusts might be okay on a 15-knot day, but a 10-knot gust on a 30-knot day is an entirely different kettle of fish. Quite frequently during stormy conditions at home, we’ll let discretion get the better part of valour and give sessions a miss when the gusts seem excessive.

As a storm front approaches, you should be able to see a giant black cloud looming on the horizon in the direction the wind is coming from. Depending on the speed of the system depends on the amount of time you have to make a decision. If you’ve checked the weather before hand and know the intricate details of the encroaching storm, you should have some idea about its effects.

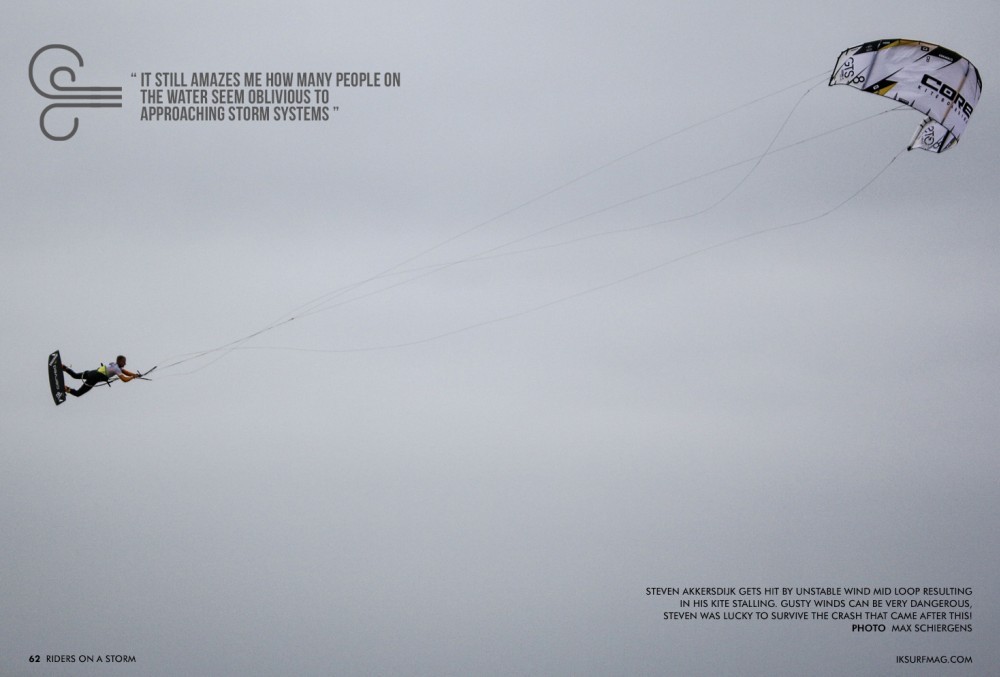

It still amazes me how many people on the water seem oblivious to approaching storm systems, and how many people get caught out. The safest thing to do is to get off the water before the weather front hits. Get your kite out of the sky and head for cover as usually a ton of rain is incoming too. It’s always better to be overly cautious than not, after all, we all want to live to ride another day.

I’ve personally witnessed numerous storm fronts over my many years at the beach, and on the water, sometimes they will move in slowly, other times they will seemingly hit almost instantly. The overruling element they all share is unpredictability. Sometimes they can amount to just a bit of rain, other times they might see a wind shift of a full 360 degrees as they pass through.

The worst instances are when the wind increases quickly and sharply catching many kitesurfers out. With a kite in the sky, it is hard to avoid a storm front when it hits; kites aren’t like windsurfing sails that we can merely lay flat and wait for the storm to pass. No matter how much depower the manufacturer claims the kite has there will still be pull on the kite when things get really wild, which is why it is best, if you can, to get to the beach, get the kite out of the sky and hunker down whenever you see storm clouds approaching.

When you see the pro’s pushing the envelope in nuking winds in Cape Town and you think you can emulate that at your local beach, you need to be acutely aware of the consequences and risks involved. Cape Town is a weird freak of a place that offers nuclear winds with a fairly predictable nature. A 40-knot day there is entirely different from a 40-knot day at your local spot when a storm front is pushing in.

There are two hard and fast rules for kiting in strong winds, which you should always bear in mind. When launching ALWAYS launch your kite closest to the sea, by doing this, it means you can keep your kite LOW and walk to the water. If you do the opposite and launch your kite towards the beach, you HAVE to swing your kite back over your head towards the sea in order to head out.

This motion is exactly what you do when you want to do a jump, and in most of the accidents I have seen in strong winds, this is what causes problems. You’re on dry land, you swing the kite and get lofted and land on the beach. ALWAYS launch towards the sea and keep the kite LOW and GO.

If you are on the water and you do get hit by a sudden increase in the wind speed as a storm cell hits, again keep the kite on the deck, right at the edge of the window on the sea or the beach. When the kite is in this position, it will drag you along the surface at worst. If you put the kite up to the zenith, often mistakenly called the ‘safe position’, there is a real risk you can be lofted into the air. Even if you fully depower your kite, there is a chance it can invert and then unleash all manner of hell.

Keep the kite low and at the edge of the window however and there is no chance of being lofted. If you are getting dragged releasing the kite in this position is much safer too. If the worst comes to the worst, ditch the kite if it is safe to do so your life is worth far more than a kite.

Risk Management

Now you have, hopefully, a better understanding of the weather systems at play, a subject as a kitesurfer you should study as much as possible, it’s time to look at risk management. Every kitesurfer on the water should be acutely aware of the importance of risk management. Kitesurfing is a dangerous sport, and inherently there is a very real risk of serious injury and even death by taking part in it.

As with anything, such as wearing the seatbelt in your car, remaining sober and driving according to the speed limit you can manage these risks to improve your chances of survival in any given situation.

The weather, your kite gear, risk management, your personal protective equipment (PPE), and your own skill will all have a role to play in keeping you safe. When was the last time you undertook a risk assessment of your kitesurfing spot? Have you recently thought about the “what if” and “what then” and how you would handle those situations? When was the last time you checked your safety release, carried out a full service on your kite bar and lines and a thorough inspection of your kite and PPE?

These are things we should be doing all the time as kitesurfers, not once a year, but every session. Don’t just check to see if it is windy according to WindGuru. Take a look at an isobar map; understand how it works, look to the local meteorological office for information about storms and weather fronts. Check where your wind is coming from before it gets to you. Beware any rain forecasts that may appear midway through your planned time for a session. Look for gusts and potential wind shifts, really start to see the weather as a whole rather than a quick glance at the local weather station and what might be happening at your local beach.

Then before each kite session, you should always start with a site assessment, how does the beach look, has the tide and currents shifted anything, are there new obstacles in the way? Is the wind direction normal, does a shift in direction bring new hazards into play? If you do get hit by a gust and lofted where will you end up, what will you do and how will you react? Are there other beach users to consider? How windy is it and what sized kite should you be flying, an anemometer can help here if you don’t possess the knowledge to make a call based on the water state. Be sure to check the wind speed at the water's edge, not in the car park or at the top of the beach where the wind can be accelerated and gusty.

Questions like this should run through your head every time you check the conditions when you get to the beach. As you unroll your kite check the pigtails, bridle attachment points, bridle lines and wingtips for signs of wear. Give the canopy a once over and finally pump it up and check it is holding air if you always pump your kite first by the time you have done your lines you should notice any significant air loss. Run your lines out each time carefully looking for nicks or blemishes or signs of fraying, any damage to a line should be immediately addressed. A snapped line out at sea could lead to a potential fatality from exposure if it is cold and you have a long swim in.

Check your chicken loop release is functioning and check your depower line is in good order. All these things sound like they take time, but in reality, as you practice them they can take mere minutes and are things you can run through as you set up. Get into the habit of doing this every time you set up, but also when you pack down, that way any damage you incur to your equipment during a session can be fixed before your next outing. There is nothing worse than setting up only to find a tear in your kite or damage to a line that you should have spotted when you packed up at the end of a session.

Having checked the weather extensively, done a sound site assessment and given your gear the once over put on your wetsuit, harness, impact vest and helmet which you should be wearing and check those elements too. The webbing on harnesses can wear through; a wetsuit full of holes won’t keep you warm during a prolonged swim either. Always ride with a kite knife, you never know when you will find it useful, check it isn’t rusty and can still cut through kite lines, keep some old pieces of line handy for testing and make sure your knife works, it can save your life.

Impact vests were compulsory at this years Red Bull King Of The Air and they make perfect sense to wear in high wind situations. We recommend a helmet too and will be doing a study in the effectiveness of these basic safety devices in a future issue.

All of the above is necessary risk management before your session, it should become second nature, you’ll be a better kitesurfer for it, and you’ll be safe in the knowledge you have done everything you can to have as safe a session as possible.

However, don’t stop there, on the water keep an eye out for other kiters, look before you turn (I’m blown away by how many people still don’t do this). Give way to riders on the water and learn the kitsurfing rights of way and adhere to them. While you are kiting keep an eye out for dark clouds bringing rain and frontal winds. Be vigilant and again you’ll be a better kitesurfer for it.

In recent years I have seen more and more riders pumping up bigger and bigger kites on windy days. I believe there are a few reasons for this. Kites are better at depowering than they were before, so you can get away with a larger kite. However, when it is at the limit of its wind window you have no margin for error should the wind increase. Always try to fly the right sized kite for the specified amount of wind according to the manufacturer.

Believe it or not, they investigate those wind ranges extensively; they need to be accurate for various reasons, so stick the recommended wind strengths for a kite, don’t risk going out overpowered for the sake of a session if it is too windy for the kite you have. It just isn’t worth it.

The other reason for larger kites is devices like the Woo and the PIQ, these tools measure your jumps and give you rankings and personal bests and allow you to compete with your friends. While on the one hand these new pieces of tech have gamified kiting, bringing a new lease of life to many kiters and adding a huge element of fun. There comes a time when you reach the limits and the only way to surpass them is to put a bigger and bigger kite up in windier and windier conditions.

At least that’s what some people think; huge jumps are often easier achieved through improved technique and skills. A coaching session with Lewis Crathern, for instance, will yield far better results on a small kite than just chucking up a 12m kite on a 7m day. Not only will your skills improve you’ll also greatly reduce the risk you are imposing on yourself, others and your loved ones…

It’s tough, especially with images like the ones we see in magazines and indeed this article. It’s tempting to push the limits and cast risk aside when we know that Nick Jacobsen jumped 28m and you’ve only jumped 10 and your mate “Dave” has jumped 12m and is taunting you down the pub about it. Is it worth your life to take that risk and throw sensibilities to the wind for a number on an app? However Nick is an expert in risk management, if he weren't’ he wouldn’t have survived the many crazy stunts he has done. Nick carefully assess every given situation he is in for risk and mitigates as much of it as possible to create a safety buffer zone.

When you consider the accuracy of these devices too, it adds further questions. Inherently we have found them to be a good “guide” for jump height, but not entirely accurate. The accuracy seems to vary between each device too, so next time “Dave” tells you he jumps higher than you tell him his device is reading higher than yours… 😉 This is the reason some pros will ride with several devices on their board and then keep the data from the device that recorded the biggest jumps…

Riding storm systems and frontal winds is a risky business, make no mistake about it. You need to educate and prepare yourself as much as possible to reduce that risk, you can’t control the wind, but you can improve your knowledge of how it works. You can control the state of your equipment, and you can control your choices over kite size and where you kite. There are many elements within kitesurfing that are totally within your control; you just have to be willing to seize them.

We’ve asked four of our friends, Ruben Lenten, Lewis Crathern, Joshua Emanual and Steven Akkersdijk for their input. Each and every one of them is an expert at riding in high winds. Ruben arguably has made a career out of it!

What do you love most about kiting in strong winds?

Steven Akkersdijk: I’m a fairly big guy (almost 2m tall), but riding in stormy conditions makes me feel so small. Being tossed around like a puppet on a couple of strings and fighting the elements just gives me an unmatched feeling. I mostly love it because of the adrenaline rush you get. Most of the time you’re in control of the kite, but when the wind gets really powerful, the kite takes control of you. It’s like getting on the back of a bull and trying to hang on for the ride!

Ruben Lenten: When the wind is nuking I am in my element. There’s no feeling like it, riding on a wild sea and boosting off waves with maximum speed and power in order to fly the biggest you can. It’s all about timing. Building up as much speed as possible and edging hard towards your takeoff spot and then yanking that kite upwards and onwards. YIIIHHHAAAA!!!

Joshua Emanuel: When I kite in high winds the thing that gets me most pumped is knowing I will be able to boost huge and throw some loops. This gives me the best adrenalin rush in the world; there is nothing that can give me the same feeling as megaloop does. Strong winds get even better when there are some decent size kickers for me to hit.

Lewis Crathern: What I love about kiting in strong winds is the amount of focus required for every given 100th of a second. As a keen all-round sportsman, there is nothing I have ever done that encapsulates ‘hand-eye-coordination’ more than kiteboarding in a strong wind. There are many constantly changing variables that need calculating instantly, the water surface, wind speed, wind angle, tension feedback, kite shape, altitude, etc. All the senses come into play the sound of the wind, yes even smell comes into play, in some places. Especially where the wind blows over land first such as Cape Town you can smell a change of wind coming, evening wind about to get shit! Taste is an obvious one too; you probably blew it if you’re tasting salt water!

What precautions do you take safety wise?

Joshua Emanuel: Before my session, I will always do some stretches as well as warm up exercises. My biggest precaution that I take is riding in my impact vest, which helps a lot in the big crashes or even if get knocked out I will still have some flotation until help arrives.

Steven Akkersdijk: When the wind is strong I always take extra care when attaching my lines and doing a quick check-up to make sure everything is perfect. You should also always make sure you keep enough distance from any obstacles. This means on the beach, trash bins, benches, sea walls, etc. but also on the water keep an eye out for other riders and of course the beach!

Lewis Crathern: I love my impact vest, now I feel like I can take any crash - I’m invincible again! Well, I persuade myself that anyway or otherwise I could not go out and give it 100%.

Ruben Lenten: Well, I have been flying power kites on the beach since I was ten years old and started kiting when I was twelve, so it’s definitely my years of experience that make me feel safe out there.

Of course riding storms is not for everyone as it comes with significant challenges for the body, mind and gear. Always before I go out, I make sure my body is trained well so that my legs and core are strong enough to deal with big landings and wipeouts. I always keep a close eye on the forecast,Windytv shows me what I can expect and which spot will work best.

Always try to kite with a buddy and let someone know you’re going on the water. I also prepare mentally by thinking about what I want to achieve each session and then visualise my way there beforehand. Before I hit the water, I make sure I do a proper warm-up so that my muscles are ready to rock and roll. Some people don’t even know how to do a warming up…it’s crazy.

It’s also very important to check your gear properly, so make sure you don’t have any damage to your lines. Here is a good tip, squeeze them when you’re laying them out, and you’ll feel an uneven surface if the line is damaged. Also, it is critical to scope out the area for any obstacles and people downwind so you keep plenty of space when prepping and launching. Last but not least check and try your safety system to make sure it’s functioning properly, so that’s your chicken loop release and your leash release.

Oh and make sure you have your knife in your harness to cut lines if needed. When launching, get some help when possible and keep one hand on your quick release. Never hesitate to pull if something doesn’t feel right or doesn’t go according to plan. The kite will be fine and so will you, most importantly.

Have you ever had any real nightmares in high wind conditions?

Steven Akkersdijk: I’ve been lucky enough never to get stuck in a nightmare situation. To be honest, I had a pretty sweet dream (was a nightmare for my family and friends though). While competing in RedbullMegaloop Challenge in 2015, we had a challenging 40 knots with gusts up to 45-50. Completely overpowered on my 8m, I was pulling some megaloops and all of the sudden the wind dies in the middle of my loop.

This resulted in a big crash and me getting knocked out. I woke up a minute later with two rescue swimmers who took me to shore. Had some short-term memory loss and water in my lungs, which resulted in a sleepover at the intensive care. Bottom line, take care when you ride in gusty conditions, the gusts can take you up quicker, higher and further than expected. While the wind holes can take you down quicker as your body can handle.

Lewis Crathern: As far as I am aware, to call it a nightmare one would have to remember it, so my big crash doesn’t count? Jokes aside that was a big one, but I’ve crashed worse than that at least 20 times in my career. That one was just an unlucky back edge kainer. I have been in situations where I think “Shit I’m not sure I can take this” and that’s only been as a squall comes over, or black clouds pass. During the early days, this has happened, and it would be quite scary.

Joshua Emanuel: Yes I had a big crash last year when my kite didn't catch me in a loop. As I dropped down, I kicked my board and braced for impact. It happened so fast that I didn't even remember the impact or what actually happened, the photographer Max Kamolz filled me in when I got to the beach. This explained why my nose was bleeding as I couldn't remember anything. I came down from 17.5m and slammed into a 5ft wave that was about to break. This resulted in my hand slamming into my face knocking me out for a few seconds, as well as tearing my ACL and cartilage in my knee.

Ruben Lenten: Over my 17 years kiting I have definitely been in positions and places I shouldn’t have been in, but mostly due to my stubbornness and craziness. Back in the day, you could get away with a lot more than nowadays. If you mess up now with something stupid, you’re just stupid…and someone will probably kick your ass because the spot will close. I have been swimming from way too far out, even when I was only 13 years old. Or landing on the beach after a jump is the worst…and so idiotic. It’s easy to go further out and keep plenty of space between you and the beach and or other kiters.

What should the less experienced kiter be looking out for and have you got any advice for them?

Joshua Emanuel: In strong winds, you need to know what the conditions are like. Is the wind gusty? What direction is it blowing? What size of surf are you comfortable to ride in. Make sure your body is fit so it can handle the harsh conditions that you will push yourself in.

Steven Akkersdijk: When you go out in these conditions you should always look behind you for the cloud formations. When you see dark clouds coming take extra caution and if you get overpowered head back to the beach and land your kite. Also, make sure you always keep enough space downwind and ride with friends. Not to scare anyone off, but they might need to rescue you from the water one day…

Ruben Lenten: The less experienced kiter should practice more and more in calmer conditions and build up confidence. Please practice releasing your kite from time to time…it seems like a pain in the ass but get good at it. It takes a matter of minutes but can save your life. Keep looking, helping and learning with each other. We all love this sport, so let's make it last and make an effort.

Lewis Crathern: Remind yourself that you can always release. In the slightest moment of uncertainty, my hand moves down to the chicken loop ready to get rid. Be ready and try to calculate ahead of time if an object or situation might not be ideal. Time is your friend.

Also, a massive tip for handling strong winds is to fly with the kite LOW in the window. I ride around with my kite barely above the water when it’s nuking. Bringing the kite above you as you get overpowered is a classic mistake it only brings your weight further up and off the water, which results in less control and a good tea bagging…

A final word

The pro riders are just that, pro riders, they don’t have a 9-5 job, they kite 9-5 every time it is windy. Guys like Lewis Crathern, Steven Akkersdijk, Ruben Lenten and Joshua Emmanuel are more at home 50 foot in the air upside down mid kiteloop than I probably am in front of my keyboard typing this. Does that mean you shouldn’t go out there and send it on the next windy day?

Of course not, what we want to convey is that while you may have all the equipment needed to launch into a massive jump in the middle of a howling storm, it’s best to build up slowly to that level, assess the risk and keep yourself safe at all times. The sharp rise in deaths and accidents at the beach cannot be allowed to continue. The brands have done everything they can to work on the safety aspect of our sport. Now, we as riders need to ensure we keep ourselves safe; you can ride as hard as you want, just manage the risks to mitigate the dangers and live to ride another day…

By Rou Chater

Rou has been kiting since the sports inception and has been working as an editor and tester for magazines since 2004. He started IKSURFMAG with his brother in 2006 and has tested hundreds of different kites and travelled all over the world to kitesurf. He's a walking encyclopedia of all things kite and is just as passionate about the sport today as he was when he first started!