Behind The Brand - Airush

Issue 58 / Tue 9th Aug, 2016

Ian MacKinnon talks to Clinton Filen and Marc Schmid from Airush about the brand, their ethos and how they see kitesurfing developing in the future.

Airush are one of the original kiteboarding brands. However, for the brand based in South Africa’s kiting mecca of Cape Town, its role as one of the sport's founding fathers is no excuse to rest easy. A ceaseless quest for innovation is an inseparable part of the company’s makeup. For kiters worldwide, that out-of-the-box thinking spawned a continual flow of groundbreaking concepts that shaped the sport.

The design-led company - on the “big side of medium” within the industry - has paradoxically never sought to transform its innovative prowess into becoming a kiting behemoth. Rather, its unshakable goal is to produce the best, simplest, most durable lines at the cutting edge of shape or technology, whether for the crucial recreational customers whose loyalty drives volume and economic viability, or fanatics specialising in any of kiting’s multiplying disciplines.

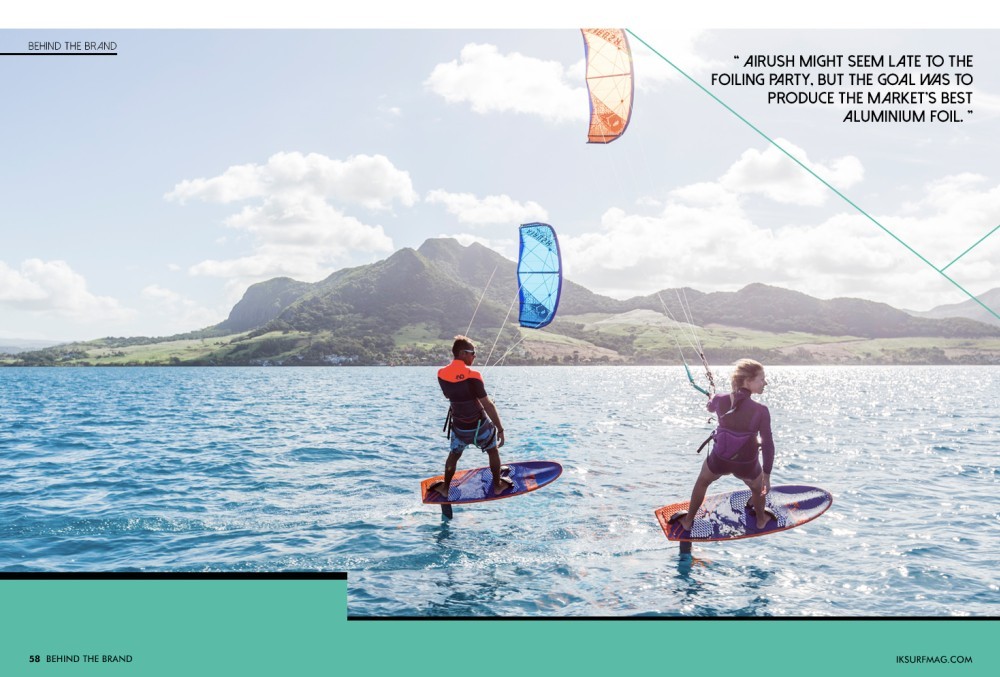

In keeping with the Airush ethos, it is tweaking what it hopes will be the lightest production tube kite, possibly a single strut affair, making it ideal for light wind wave riding and foiling. It has just launched two hydrofoils, the all-carbon Team foil and the aluminium-masted and fibreglass-winged Core foil. Airush might seem late to the foiling party, but the goal was to produce the market’s best aluminium foil. The beautifully engineered and styled Core looks stunning and is priced very aggressively.

Airush team rider and leading foil racer, Julien Kerneur, helped design the premium Team foil and carbon board. Likewise, the small roster of hard-working team riders, such as world champions Alex Pastor and Bruna Kajiya, contribute their expertise to kite and twin-tip development. It is an Airush guiding philosophy that customers can buy kit identical to that used in competition by the brand’s stellar team. That clear-eyed vision putting customers at the heart of the process also translates into a tightly-defined kite line - the uncompromising Razor “C” kite for freestyle or the Wave for surfing, for instance - rather than claim ‘one kite does all’.

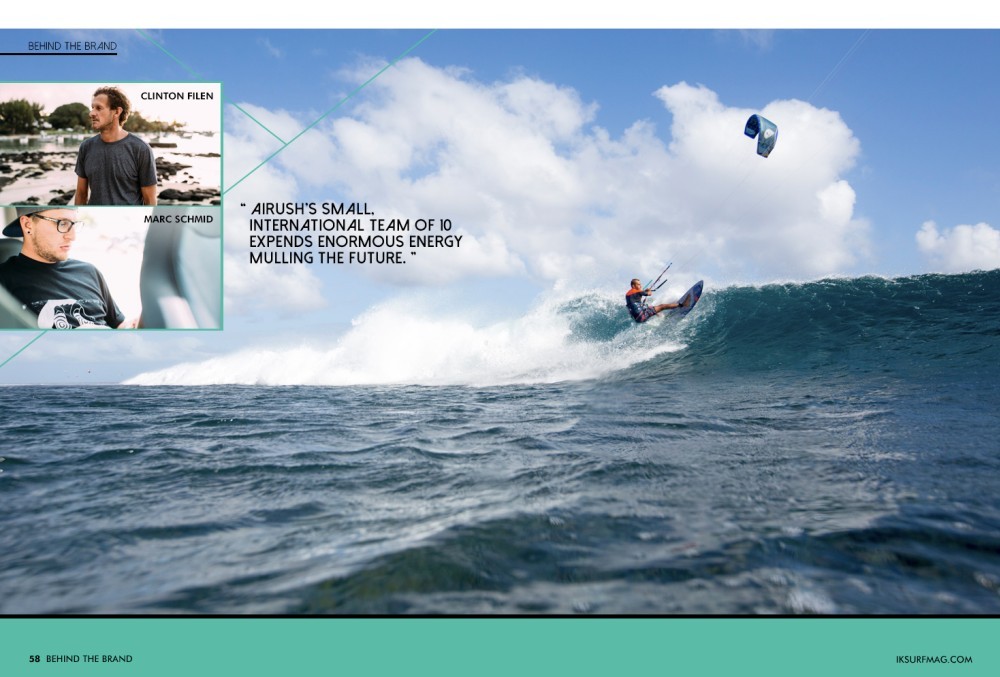

Beyond kiters’ narrow interests, though, Airush’s small, international team of 10 expends enormous energy mulling the future. Be it increasing inclusivity by drawing in more women, or seeking to grow kiting’s social-lifestyle side akin to surfings broad appeal. Similarly, the environment is a top priority. Airush believes developments like its Load Frame Technology that braces the kite canopy, dramatically reducing stretch and effectively doubling lifespan, is one way to cut our carbon footprint. It is also launching an “eco” board range. In the same vein, Airush heavily supports industry body, the Global Kitesports Association (GKA), as it tries to resolve the current chaos in competition kiting and shape the sport’s future.

On the sidelines of the Airush photo-shoot and “product development” week in Mauritius, I sat down with Brand Manager Clinton Filen and Marketing Manager Marc Schmid to tease out the details.

Airush has been around since the beginning and was always innovative. How important is that today?

Clinton Filen: If you look at the heritage of everything we do as a group, you see that our company is pretty much run by designers. From Svein Rasmussen (founder of Starboard, the parent company of Airush) who is pretty much a product designer, to my background, I’ve always been a product designer. It’s part of our DNA.

Marc Schmid: Even our team riders are product driven; they’re heavily involved in how a product performs. We don’t just send them a board and let them deal with it. We ask them questions to keep them thinking as much as possible on how to develop something, how it could perform better.

Mark “Paddo” Pattison, your kite designer, spends much of his time in Bali. How does that work in designing new models or lines?

CF: In terms of process, I work as design director. I’ll write a brief for him. At the moment we’re developing a kite for foiling and light wind wave riding. I give him a framework of requirements. I won’t say it needs to look like this or have this many struts. That’s up to the designer to work within the brief.

MS: First the prototypes go through his hands. He waits until he gets quite near to a finished product with, say, versions A, B and C. He would then pursue version C if that met everyone’s demands.

CF: Generally kites get built in the prototype loft in China, where our kites are made. In five to ten days we can get a sample made and shipped. “Paddo” gets kites made in batches of six or eight at a time, whether it’s the Wave, or Union, or the single strut. We’ve a very clear strategy: we have our “speciality” products and our more versatile “core” products that are multi-functional. We’ve two all-round kites, the Lithium and the Union. Our speciality kites are the Wave, the Razor for freestyle and the Diamond for women. Some brands will claim their kites do everything. That makes no sense to us. For us, it’s paramount to highlight to the customer what it’s really good for.

You mentioned you’re working on a light-wind wave and foiling kite?

CF: That’s one of the challenges, exploring all the niches. You can think of ten ideas, but maybe only one will be ideal for the market. We’re looking at the way people are riding. For example, we’ll go to Tarifa and spend time with Alex Pastor, and you’ll see people are focused on high-wind strapless or freestyle. And then you go to Thailand…if you can add two extra knots to the bottom end for the average customer, instead of getting one weekend a month they’ll get two, doubling their water time.

MS: That was the thing with the Sector. It doubled people’s water time. That was unheard of, or not paid attention to by most brands.

CF: It’s the same with Mark Pattison living in light-wind Indo; you get versatile out of necessity.

So now you’ve developed the foils. Where does that leave the Sector and the light-wind boards?

MS: It’s quite polarised. I was in Hood River [USA], a notoriously windy spot, and maybe forty percent of the kiters there were foiling. But then when I went to Florida, a notoriously light-wind area where it’s less than waist deep in many areas, that’s where the Sector and light-wind twin-tips shine. Foils were non-existent in Florida. Finding the right products for the right places is essential.

Let’s talk about your foils; one is aluminium with fibreglass wings, one is full carbon?

CF: The architecture and geometry are basically the same on both, though the aluminium one has a shorter mast, which works well. It’s 83cm on the aluminium and 93cm on the carbon. We’ll also bring out a 60cm mast in aluminium. One thing that I wanted to do was build the best aluminium foil on the market. So far the feedback has been really, really good.

MS: We’re finding that even more avid foilers who’ve tested it are finding it perfect for just going and riding. What more advanced riders say is that you’re going to spend an extra two hours to learn on it, but spend years riding it.

Since foils tend to be pretty expensive, how are they priced?

MS: I see foiling has a huge place, but to foster broad-based participation you need to bring down the cost of ownership to something reasonable. That’s a big thing for us. The aluminium foil doesn’t come at an insane cost. The carbon foil and carbon board is premium and will be around $3,500 USD. There’s a different focus on the free-ride market with the aluminium foil and Core board, which will sell for around $2,000 USD.

CF: On pricing, particularly with kites, a big thing for us is the longevity. Three years ago we introduced the Load Frame. That pretty much changed everything. It’s been our biggest single step as a company. It’s not how good a kite flies for the first three months; it’s about how good it is after two years. That’s when you see the effect, in how well the kite still performs because we’ve fundamentally changed the way the kite functions. You’ve stopped relying on the canopy. It’s a huge challenge to stop it from stretching. If you crash a kite, the shock wave running through the kite will stretch the canopy. With the Load Frame, the canopy will give a little bit then go back to its original position. Without it, you lose the kite’s conic shape as it gets older and stretches. The shape keeps the kite stable, so you see stability, performance and steering issues. The Load Frame means you’re not using the canopy to retain those performance shapes. We’ve pretty much doubled the kite’s lifespan. Just like boards, they’re lasting years. I think we’re the only company to offer a two-year warranty on twin-tips.

You get your twin-tips made at Playmaker in Taiwan. How does that work?

CF: We’ve a press and CNC machine in Cape Town that we can make prototype boards on, or we can get prototypes made in Taiwan, depending on what we’re trying to achieve. In board design, there’s a certain level of fashion. We were just discussing channels versus no channels. Channelled boards do land more comfortably for freestyle, as much as we might argue channels create drag. But innovation goes in circles, and a change in kites might bring about a change in boards, or a change in disciplines, like “big air” or a rise in twin-tip racing.

Are your riders, such as Alex Pastor and Bruna Kajiya, heavily involved in development?

CF: Honestly, if you want to build the best freestyle board in the world, you can’t go out and test it yourself. That’s the reason we have the Team Series because we want to offer a zero compromise board. Even Alex Pastor’s bindings are identical to those he wants to use.

MS: It’s important to us people can walk into a shop and buy a board and kite, anything from our Team Series, and you’re getting a premium product.

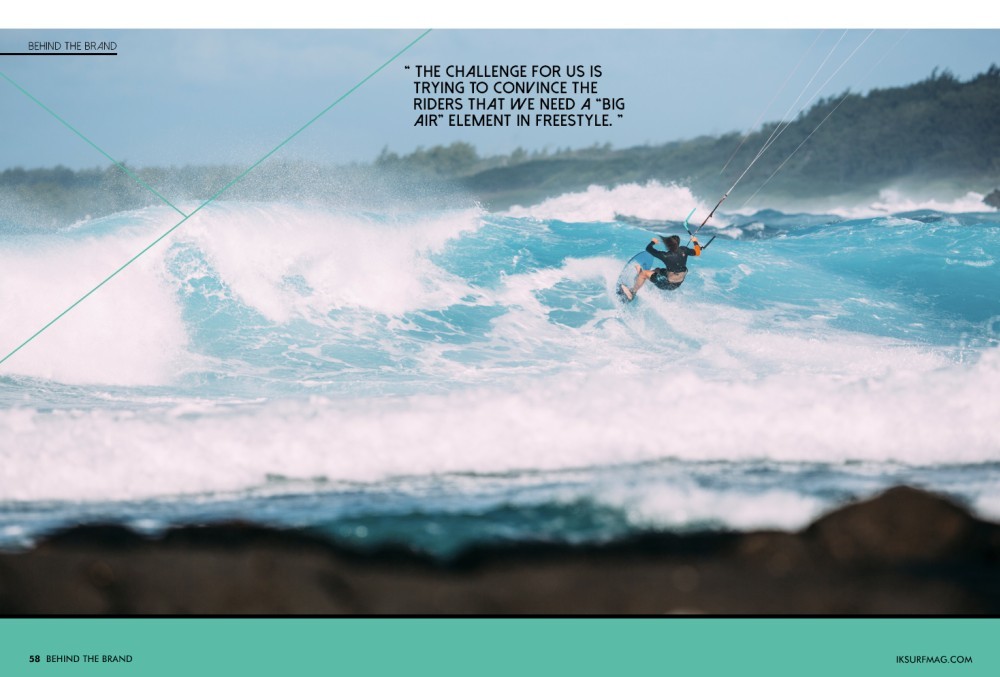

How does the current state of kiteboarding competition affect you as a brand and the products you offer?

CF: For us, the GKA is a really strong organisation. The disruption in the kiteboard scene has unified the industry and the brands. As an industry, we want to continue running kiteboarding events, and we’ve put forward a strong concept of what we want to see; in terms of developing freestyle, seeing strapless wave riding and also strapless freestyle, plus watching the racing scene grow into something we can take to the Olympics. So we’re looking at three key disciplines in where the sport’s going to go. I work within the GKA to develop all the competition formats. I discuss it with the riders, our team and our competitors all the time. If you look at freestyle, the challenge for us is trying to convince the riders that we need a “big air” element in freestyle. For the riders, freestyle is all about a low, technical style of riding. With the GKA Wave and Strapless Pro kicking off in Tarifa, and Mauritius and Brazil looking strong, we’re also talking to Liquid Force who’d love to do an event in the Hood River in the US. There’s so much energy around it.

Are you developing a board specifically for strapless freestyle?

CF: It’s evolving as a discipline, so we will work on it, but it depends on the rider. For example, when the Slayer was brought to market, that was specifically for flat-water freestyle. We worked on that with Reider Decker with the aim of bringing strapless riding to a broader range of people. We did that three years ago. Now it’s interesting to see how many people have taken up strapless riding. Back then it was a bit niche. Everywhere you go, people are riding strapless these days.

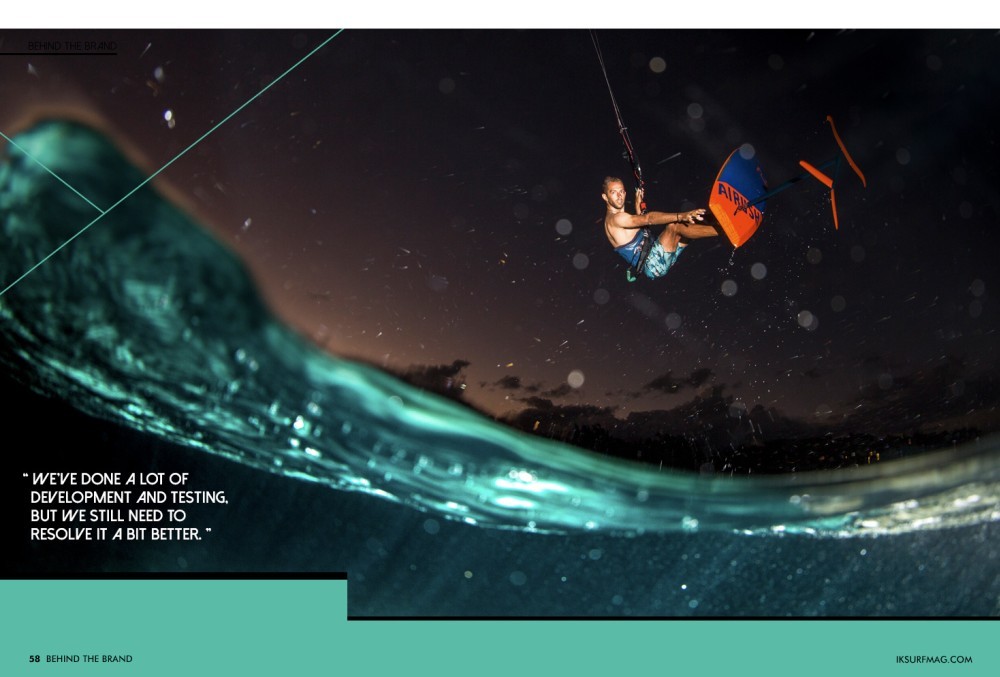

Do you ever think about getting back into foil kites? You used to make foils for snow?

CF: We continue to look at it. However, the challenge is that commercially we want to sell products to everyday customers and for us, foil kites are very, very niche. We were first with the Zero, a strutless kite. But the commercial limitation, for everyday customers, was the relaunch. At the moment we’re working on building the lightest inflatable kite on the market, one that can stay in the air in really light winds. That also has applications for wave riding, as well as foiling. If you’re riding towards the kite and it’s drifting, it has to be able to stay in the air in, essentially, eight knots. We’ve done a lot of development and testing, but we still need to resolve it a bit better.

Does all the innovation help grow the business for Airush?

CF: For us, it’s good. We don’t want to be the biggest company. It’s not about size; it’s about being able to influence the market. We’d like to be a top three brand, but I’d happily forsake size for making the right decisions. It’s challenging growing when you make twin tips that last five to ten years and kites that last twice as long as before.

Over the previous five years, our average growth is 20 to 25 percent. The industry’s growing at around 5 percent. Participation is still growing, and schools are growing, so that’s good for us. Indeed, we find at a school level, the majority of students are female. So the thing is building a culture around the sport that becomes a way of life and a lifestyle. That’s why we do female clinics with Bruna Kajiya, and why we have a female range, the Diamond. It’s not going to make us millions, but if we can take that aspect of the market and grow it, overall it’s good for the sport.

Does that sense of broader responsibility manifest itself in other ways?

CF: We’re trying to push the environmental side. We’re pushing to launch the first “eco” boards range, using an organic-based resin. It’s something we’d like to see the whole industry take up, so we’re sharing it with the industry. This year we’ll launch boards built from bio-resin, with a bamboo sandwich and EPS core. That’s positive for the environment. We’re looking at the whole carbon footprint. That’s why the durability of kites and boards is so important. We’re also trying to build service centres so that people can keep using their products for as long as possible. It seems counter-intuitive. We want to sell as much product as possible, but you see the way we work. We’re not out there to be the biggest. We’re out to see what really contributes.

Thanks, Marc and Clinton for taking the time to talk to us!

Videos

By Ian Mackinnon